Category: Human Rights

Policymaking by Empathy: Interning at the State Department

By June Lee, ’21

It’s 8:10am when I walk into the office, my blouse lightly dampened by my walk under the merciless Washington, D.C. sun. As I head to my cubicle, I hear snatches of conversations on the humanitarian crisis in Yemen and the current status of peacekeeping in Mali. I can’t help but feel a secret thrill to be working alongside individuals on issues I’d only ever read about and studied in classes.

Interning at the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Conflict Stabilization Operations was, academically, one of the most enriching experiences I’ve had. Through weekly meetings, I gained exposure to the incredible breadth of concerns incorporated into the United States’ conflict stabilization efforts, from the role of women in peace processes, to the importance of intra-group cohesion in negotiations, to the efficacy of interventions by nonprofits and other third parties. No matter what project I was working on, it was fascinating to realize that here, my efforts could have a direct application for policy. Translating an article evaluating violence reduction in Colombia could directly inform the bureau’s engagement with partner organizations on the ground. Similarly, developing a digital framework on Excel depicting election violence indicators could help the bureau allocate funding and resources quickly to mitigate the risks of political violence. Over time, I also gained familiarity with the inter-agency process and overlapping departmental structures responsible for developing and implementing U.S. foreign policy.

Yet the most valuable thing I learned from my internship was the incredible depth of empathy it takes to work as a public servant in the State Department. The individuals I encountered worked on projects that directly affected the welfare of communities in countries emerging from conflict, and they were constantly thinking about the communities they were seeking to support. This mindset translated to all aspects of their work. My main supervisor related how, while serving as a foreign service officer in New Delhi, he would often bike to work with a camera, and offer to take pictures of people on the street. Their surprise and joy upon receiving a picture of themselves led to his receiving a flurry of texts and blessings every holiday. Another director, frustrated with the United States’ failure to address the humanitarian crisis in Syria, was motivated to resign and work for a nonprofit focused on human rights advocacy for Syrians and other refugees. And, during my daily commute, another officer explained how he had worked in Afghanistan for 18 years, an experience he spoke of with a hint of sadness but also admiration for the resilience of the Afghan people.

Since my internship, I’ve been determined to embrace this mindset. As a director of Stanford in Government and a peer advisor in international relations, I’ve sought to encourage more students to pursue careers in policy and public service. And, while working on my senior thesis, I am committed to developing a research paper that can be beneficial to policymakers and useful in advancing the United States’ efforts in conflict resolution.

Originally from Sunnyvale, CA, June Lee, ’21, studies international relations at Stanford. In addition to completing a Cardinal Quarter summer fellowship with the State Department’s Bureau of Conflict Stabilization Operations in the summer of 2019, June serves as the director of diversity and outreach of Stanford in Government and as a peer advisor for the international relations department. June is also an incoming honors student with the Freeman Spogli Institute’s Center for International Security and Cooperation.

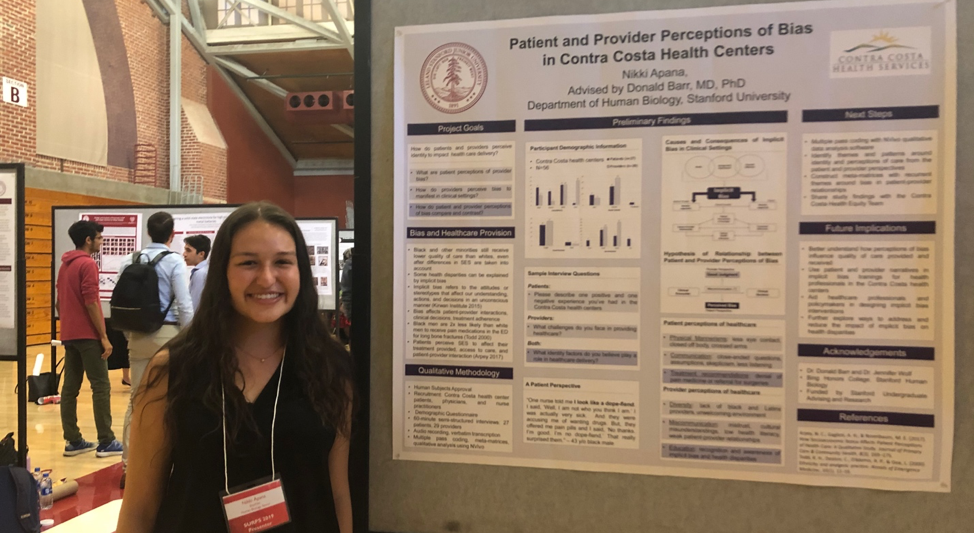

Unequal Treatment: Exploring Unconscious Bias in Health Care

By Nikki Apana, ’20

“One nurse told me I look like a dope fiend. I said, ‘Well, I am not who you think I am.’ I was actually very sick.… And they were accusing me of wanting drugs.” – James (pseudonym), 43-year-old Black male

James is a participant in the community-based research project I have been conducting over the past three summers. I have been collaborating with Contra Costa Health Services, the public health system in my hometown, to find ways to address unconscious bias in patient care. Unconscious bias refers to the stereotypes we internalize that affect our behavior, judgments, and actions without our conscious awareness. And what is so pernicious about unconscious bias is that everyone has it, yet few realize it.

Unconscious bias covertly plays out in our everyday lives. As described in Howard Ross’s Everyday Bias, NBA referees call more fouls against Black players than White players, famous Black actor Danny Glover reported struggling to hail a New York City cab after dark, and job applicants with “Black” names are less likely to receive a callback than applicants with “White” names. Bias extends beyond race to gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, age, and weight. It surrounds us every day and it is embedded in our subconscious. Even when we think we treat everyone equally, pride ourselves on promoting equality, and call ourselves feminists, queer allies, and social justice activists, unconscious bias still pervades our minds and actions.

Bias is particularly injurious in the provision of health care. Even after differences in socioeconomic status are taken into account, Blacks and other minorities still receive lower quality of care than Whites. Innumerable studies in the American Journal of Public Health and Annals of Emergency Medicine show how bias can impact clinical decisions. Physicians tend to rate their Black patients as less intelligent, more likely to abuse drugs and be non-compliant with treatment, and less likely to desire an active lifestyle and have adequate social support. Minority children with accidental injuries are three times more likely to be reported for suspected child abuse than their White counterparts. Additionally, Black and Hispanic patients are two times less likely to receive pain medication in the emergency department than White patients.

James shared a similar account of being accused of seeking drugs and being denied pain medicine while seeking emergency treatment for a liver condition. His narrative is just one of many that I collected through the community-based research project.

This project grew out of a community need to address unconscious bias. During my first summer as a Community-Based Research Fellow through the Haas Center, I helped the Contra Costa Health Equity Team develop an unconscious bias training curriculum for health-care providers. The training has been piloted with over 500 providers and continues to raise awareness about the detrimental effects of provider bias. However, many participants have still expressed concerns about learning how to mitigate their bias in the clinical setting. I consulted with members of the Health Equity Team, and together we developed the next stage of research: interviewing patients and providers about their perceptions of unconscious bias in the health centers. This study seeks to center the voices of populations that have been historically marginalized and silenced. It will also identify concrete examples of insensitive behaviors in order to offer providers specific tools for reducing unconscious bias. I have already conducted 56 interviews with patients and providers, including the one with James, and have been qualitatively analyzing these transcripts over the last two quarters with the support of the Haas Center Public Service Scholars Program and my honors thesis advisors, Donald Barr and Jennifer Wolf. In the spring quarter, I will finish writing my honors thesis and deliver a presentation and report to Contra Costa Health Services with suggestions for improving the implicit bias training.

Community-based research has taught me the value of placing community needs at the forefront of identifying problems and enacting change. More specifically, this project with Contra Costa Health Services has given me the opportunity to explore unconscious bias in medicine, as well as my own unconscious bias. I am slowly becoming more aware of my own biases and more capable of stopping biased thoughts in their tracks. All the stereotypes we have learned can be unlearned once we recognize the ways in which we hold biases, foster dialogue about unconscious bias, and continue to acknowledge privilege and self-reflect on our actions and attitudes. Biases can be broken. With time and effort, injustices like those James has faced will become the exception rather than the norm.

You can find out more about your unconscious mind and take an Implicit Association Test (IAT) at Harvard’s Project Implicit.

Nikki Apana, ’20, studies Human Biology with a concentration in race, ethnicity, social class, and public health, and a minor in Spanish. Originally from Concord, California, Nikki has spent the last three summers in her hometown working as a Community-Based Research Fellow through Cardinal Quarter on issues of bias in the health-care system. At Stanford, Nikki serves as the lead Cardinal Service Peer Advisor, president of the Polynesian dance team Kaorihiva, and residential assistant in Branner Hall. Nikki has also worked as a SHAR(ED) volunteer throughout her Stanford career, was a Branner Hall Service Scholar, serves as a Cardinal Free Clinics Patient Health Advocate, and is a member of the Public Service Scholars Program.

Engaging the Public in Advocacy for Survivors of Sexual Violence

By Elizabeth Kim, ’22

3, 2, 1. We were rolling.

It was only my third week as End Rape on Campus (EROC)’s campus data fellow, and here I was, speaking to hundreds of people as I explained concepts that I had only grasped the nuances of a week earlier. I was aided, of course, by my boss: EROC Policy Director Ever Hanna, an attorney whose detailed knowledge of government, law, and sexual violence advocacy never ceased to awe me.

In this Facebook livestream, however, we were sitting side by side, co-hosting an informative Q&A on topics that ranged from affirmative consent to the Clery Act, a law that aims to provide transparency about campus crime policy and statistics. Though I’d spent many hours anticipating and rehearsing the answers to questions tweeted to us from all over the country, I was terrified of saying the wrong thing. Could my new understanding of this incredibly complex issue fail me, forever tarnishing the reputation of this organization that I already loved so much?

My primary project during the summer with EROC was helping establish an accessible, accurate, self-sustaining School Accountability Map, with the goal to make every U.S. college and university’s sexual assault policies and history accessible to the average college student. Because every school in the U.S. interprets Title IX differently, and few make that information accessible to students, the map will improve transparency and put power in the hands of student survivors. It was my job to develop and launch the Map Volunteer Campaign—to recruit, instruct, and vet the research of the volunteers who would collect information on each school. This livestream was meant for these volunteers, many of whom identify as survivors themselves, as they navigated the gargantuan task of researching and processing their school’s Title IX policies.

The goal of the livestream Q&A was not only to inform our volunteers, but to excite and motivate them about the work ahead. We wanted to empower volunteers with answers to their questions, but also show them that they already possessed the intelligence, courage, and persistence needed to educate their own communities about their school’s history with sexual violence.

Fun, informative, and relatable. These were the words I chanted in my head as our communications director counted down the seconds to us rolling, but soon I forgot about them. I rattled off different definitions, fielded a viewer question about due process, and chimed in on Ever’s explanation of how federal agencies can mandate different interpretations of Title IX. I felt myself falling into the rhythm that I so often enjoyed while watching talk show hosts vibe with guests they knew well.

I came out of the livestream that day not only with a more profound sense of confidence, but also an important realization: fully understanding something means you can explain it to another person. And an explanation requires a willingness to engage and put yourself out there.

This is the sort of heightened confidence I draw from as a student seeking to raise greater awareness about Stanford’s own culture of sexual violence. Whether I’m writing an Op-Ed or participating in an awareness campaign, I’ve realized that there are many ways to engage the community—each as important as the next.

Originally from Boston, MA, Elizabeth Kim, ’22, majors in economics at Stanford. In addition to her service through the Cardinal Quarter program as End Rape on Campus’s data fellow during the summer of 2019, Elizabeth serves as a French language conversation partner at the Stanford Center for Teaching and Learning and chairs philanthropy and alumni relations for Sigma Psi Zeta Sorority.

How an Urban Studies Class Made Me a Better Engineer

By Katherine Erdman, BS ’19, MS ’20

As the countdown to graduation began, I, like many other Stanford seniors, was eager to complete my general education Ways of Thinking/Ways of Doing. As I planned my fall quarter, I was on the hunt for a class that satisfied my last unfulfilled requirement: Engaging Diversity. There were almost 200 classes to choose from, but I settled on Urban Studies 164: Sustainable Cities. I had a mild interest in environmental technology, so I decided to give it a go.

On the first day of class, I was surprised that the focus of the course wasn’t on hydrogen fuel cells and electric cars. Rather, environmental health was just one of four aspects of sustainability we would be tackling, in addition to cultural continuity, social equity, and economic vitality. This broadened definition of sustainability, going beyond greenhouse gases and air quality indexes, was especially meaningful on the day we talked about transportation in the Bay Area. Like many other computer science students, I spent a summer interning at a large technology firm just miles from campus. I did not have a car and benefited from the shuttle service provided as part of the job. Every morning, I walked a few minutes to the nearest stop, hopped on the bus, and arrived to work without issue. I brought this up as an avenue to increase sustainability. The buses were quite full and eliminated at least hundreds, if not thousands, of mostly single-occupancy cars from the road. While my classmates agreed that the shuttles helped with environmental health, I was challenged to also consider the soaring housing prices near newly placed shuttle stops that make longtime residents unable to afford to stay. They are often replaced by tech workers, eager to be closer to the shuttle stop and able to afford higher rent. Perhaps certain shuttle stops trade off cultural continuity in pursuit of sustainability?

Through many eye-opening discussions, I more clearly saw the effects of sustainability efforts within the social and cultural realms by the end of the quarter. I walked away with a new perspective, which I applied to my senior project class CS210: Software Project Experience with Corporate Partners. My CS210 team partnered with Oracle and was given the task of creating social good technology. We decided to tackle the issue of employment opportunities for formerly incarcerated individuals. Within this space, it’s easy to identify unmet needs, such as the need for technological education for someone who has been disconnected from the job market for a number of years or the need for mock interviews for someone who has never formally applied for a job before. However, my experience in Urban Studies 164 helped me understand how any solution has to fit within a larger ecosystem. I found that my team and I were challenged to look beyond economic vitality and consider the cultural continuity and social equity concerns that our solution had to address. Whether integrating our solution into the parole preparation process for the incarcerated in Australia or modifying the product’s user interface to be approachable for first-time digital users, our team attempted to address cultural and social issues that appear tangential, but are deeply connected to the product’s success.

Katherine Erdman, BS ’19, is a coterminal master’s student in computer science from Ellicott City, Maryland. During her senior year, she took Urban Studies 164: Sustainable Cities, a Cardinal Course that introduces students to sustainability concepts and urban planning as a tool for determining sustainable outcomes in the Bay Area. Katherine has been involved in the Business Association of Stanford Entrepreneurial Students, SHIFT: Healthcare Innovation @ Stanford, and she++. She is also a member of the Student Alumni Council and the Viennese Ball Steering Committee.

Queer Migrant Experiences: Exploring Self and an International Community

By Alan Arroyo-Chavez, ’19

The warm summer air kissed my face as I sat on a tree-shaded hill watching the sun set between la Catedral de la Almudena and el Palacio Real. Who would have thought that a boy from Tracy, California would end up basking in the orange madrileño sun?

Then again, this was my second time in the city. When I first came to Madrid, Spain in 2017 through the Bing Overseas Studies Program, the city charmed me with its architecture, liveliness, and people. I didn’t think I would return, but then I was offered the Halper International Summer Fellowship to work with Kifkif, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to provide aid to queer immigrants in Madrid. People who seek help from Kifkif come from Europe, Latin America, and Northern Africa; they speak English, Spanish, French, Italian, Romani, and Arabic.

Immediately, I was put to work transcribing interviews that my supervisor, Florencia Rivaud, had conducted to shed light on queer immigrants’ experiences coming to Spain. In these interviews, I heard about queer people being extorted because of their identities and Latinx trans women being ostracized. I was shocked by the hardships that the people interviewed went through. However, these same people made a home for themselves in a new country, came to terms with their identities, and maintained positive attitudes. Many of these immigrants and their children return to work for Kifkif to help others settle in Madrid.

Listening to their stories forced me to break through the veil of comfort that living in the United States created. As a queer Mexican man, I see the community of queer refugees in Madrid as part of my own broader Latinx and queer community. However, we differ in a key way. In the United States, despite its own shortcomings, I can be open with my friends and my loved ones, and this safety is a privilege that I took for granted.

Laws and cultures around LGBT issues in places like Spain shift over time. Spain decriminalized homosexuality in 1979 soon after the fall of the Franco regime, legalized same-sex marriage in 2005, and instituted penalties for discrimination based on sexual orientation. (In comparison, there are still jurisdictions in the United States that protect an employer’s right to dismiss an employee based on sexual orientation). Because Spain has risen as one of the countries most accepting of LGBT people, Latin Americans immigrate to Spain. This migration is complicated and ironic given that these immigrants seek refuge from violent dynamics that Spain established in the first place.

I think a lot about how after 1492 Spain imposed Catholicism in Latin America, establishing rigid gender roles and solidifying hetero-patriarchal dynamics among indigenous peoples and their mixed descendants. Those dynamics continue to affect my community, including myself.

Though it continues to be difficult to unpack the relationship that my Latinx communities will always have with Spain, this Cardinal Quarter experience has been a gateway to learning more about the human rights issues that queer people face internationally. I hope to continue learning about the experiences of queer immigrants from countries outside the United States so that I can better connect with communities I consider my own.

Alan Arroyo-Chavez is majoring in Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity. He is a member of the Public Service Honor Society, a year-long cohort that provides seniors the opportunity to reflect on their public service and develop their civic leadership identities. In 2018, he completed a Cardinal Quarter in Madrid, Spain with Kifkif, an aid organization for queer immigrants.

Who Tells Their Stories: Questions of Ethics and Agency at the Southern Border

By Jenn Ampey, ’19

The room was tiny and filled with more people than the fire code allowed. Giant cameras stood on tripods at various heights, but all of them were tall enough to block my view.

I was attending a press conference for parents looking for children who had been taken from them by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). It was only my second day of work with Hope Border Institute, a human rights advocacy organization on the southern border, but already the whirlwind that was summer 2018 had swept me up; every day brought news of changes to U.S. immigration policy and the deepening insecurity for asylum-seekers under the Trump administration. In the crowd stood reporters from the Washington Post, CNN, and Telemundo. Microphones from the newspapers and networks sat atop their cameras, pointing at ten parents sitting in a line across the front of the room. They took turns speaking.

This press conference was my first (but not last) visit to Annunciation House, a shelter for recently arrived immigrants that was quickly becoming the center of media-to-parent interaction under the outspoken leadership of the director, Ruben Garcia. Struggling to balance engagement with the media and his desire to protect the newly arrived immigrants under his care, he stood nervously at the front of the room. As reporters jostled in front of me, I realized that many of them didn’t speak Spanish. On the other hand, the parents waiting to speak to us did not speak English.

Accepting the fact that I would never be able to see, I settled into my spot against a wall to listen, occasionally glancing up at the camera monitors overhead to get a picture of who exactly was speaking. My supervisor, Edith, stood next to me as farm labor leader Dolores Huerta arrived to take the seat that we were saving for her in the back. She lasted about five minutes of not being able to see anything before she stood up and made her way quietly through the crowd to the front, where she could look directly into the faces of the parents.

A father spoke emotionally about missing his son, eventually breaking down and sobbing at the table, while Ruben’s hand rested on his shoulder. In that moment, I noticed something that would preoccupy me for the rest of the summer. As the man cried harder and harder, the sounds of hundreds of camera shutters filled the air. It was a hot day, but I felt a chill crawl down my spine. Bile rose in my throat, and I turned my head away. For the rest of the press conference, I stared at the ground and tried to hold back angry tears and take in everything I could at the same time.

When the press conference finished, I helped my supervisor field translation requests from reporters who only spoke English but still wanted individual interviews with the parents. Eventually, we left and walked back to the car. I slid into the passenger’s seat with a migraine throbbing from the emotions of the day. A tear slid down my cheek and mixed with the sweat from Texas’s harsh summer heat. Day 2 of 45.

Jenn Ampey, ’19, is an international relations major with a minor in human rights, from Rockville, Maryland. She is the Cardinal Service Peer Advisor team lead and member of the WSD Handa Center for Human Rights and International Justice Student Advisory Board. After graduation and a gap year, she hopes to earn a joint law degree-journalism masters’ degree and help find better ways to tell the stories of survivors of human rights abuses, largely as a result of her Cardinal Quarter experience on the border.

Music, Laughter, and Joy: A Summer of Therapeutic Music in Senior Living Communities

By Samantha Starkey, ’19

Research shows that singing has beneficial effects on the mood, cognition, and health of older adults. These findings are the basis of my placement organization last summer, SingFit, a Los Angeles-based startup that uses technology to make therapeutic music more widely accessible for older adults. During my time interning with SingFit, I saw how one-on-one and group therapeutic music sessions in senior living communities enhance the well-being and social engagement of older adults.

At one of my group sessions at a memory care facility, there was a gentleman who at first seemed confused and disgruntled.

“I can’t sing. I don’t know the words. I can’t even hear properly,” he complained.

As time went on, he began singing along with the group, and he would suggest songs from musicals like West Side Story, once gracing us with a brief rendition of “Maria” in a mellifluous tenor voice.

One day, we sang the Andrews Sisters song, “Beer Barrel Polka.” Most songs have associated dance moves to encourage movement, and we all repeated the “Beer Barrel Polka” move throughout the song: pretending to drink a mug of beer. Afterward, with a deadpan face, he looked at me and mock-sternly cried, “You’re over your limit!” The whole group giggled.

That gentleman was just one of the many people who had a profound impact on me this summer. Working with him made me realize that patience, respect, and music can bring out talents, humor, and joy in people.

Sam Starkey is a senior studying human biology and education. Samantha served as a Roland Longevity Fellow with SingFit. At Stanford, she has been involved in several Cardinal Commitment student organizations, including Side by Side, The Bridge, and Ravenswood Reads. She is from Vancouver, Canada.

Corresponding with Criminal Justice: Letters that Brought Me Hope

By Samuel Feineh, ’19

It wasn’t until the summer after my sophomore year, through my second Cardinal Quarter opportunity, that I became more confident in who I am and what I stand for.

During summer 2017, I interned at the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project, which is dedicated to reforming prison conditions nationwide. In 2014, the ACLU filed a 34,000-person class action lawsuit against the Arizona Department of Corrections (ADC) for violating a number of inmates’ constitutional rights. After a long legal battle, the ADC agreed to reform its health care system, limit the use of solitary confinement, and provide greater access to mental health resources. When I arrived, the ACLU was monitoring the department’s compliance.

As part of the class action lawsuit, inmates could send letters to the ACLU. I spent most of my time responding to each inmate who wrote to us to supply them with resources to help them file their own lawsuits, seek medical help, or file a grievance in prison.

Hundreds of inmates wrote. Some had simple requests, and others revealed the horrid prison conditions they faced.

Reading these letters was at times straightforward, and at other times, heartbreaking. There were countless stories about inmates being denied medical coverage by private contractors, and as a result, facing life-or-death situations. In one letter, a prisoner wrote that a prison guard raped a severely mentally ill inmate, yet no investigation was undertaken.

While there was much to be frustrated about, I learned something so important from my colleagues at the ACLU: when you want to change a corrupt system, you have to start somewhere. And after you start, you keep fighting.

I spent hours on each letter, combing through the inmates’ files to send as many resources as possible. I also scrutinized thousands of documents—including medical reports and use-of-force logs—that the ADC sent us to ensure that they complied with various class action stipulations.

As part of this review process, I analyzed prison temperature logs. Each of the 15 ADC state prisons had to record the temperature at set times every day, compile the data, then send it to the ACLU each month. These records helped the ACLU ensure humane conditions in the facilities, especially in the summer months when temperatures sometimes exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The logs were routine and usually unsurprising, though we wondered if the prisons were falsifying the data because most of the temperatures ranged between 80 and 90 degrees. We had no way of proving deceit, until I found the proof.

One day, while reviewing the last few pages of one state prison’s report to the ACLU, I noticed that the facility had filled in temperature data for six dates that came after the date they had sent us the logs. The ACLU team provided the information to the judge, and swift action was taken to punish the ADC.

Witnessing how evidence is leveraged to administer justice further revitalized my hope in prison reform: through rigorous analysis, I played my part as a watchdog and made a difference.

When I came home each night to the Stanford in Washington house and told my new friends about my work, I felt my newfound sense of purpose seep into the conversation. This experience left me believing I am a change agent, and I’m excited to continue nurturing my passion. I am emboldened to keep fighting.

Samuel “Sam” Feineh is a 2018-19 Cardinal Service Peer Advisor. During the summer of his freshman year, Sam received a Cardinal Quarter to intern for his Congressman on Capitol Hill. This year, he also serves as the vice chair of programming for Stanford in Government and co-president of the Stanford Black Pre-Law Society. He is originally from Sacramento, CA.

Returning to Guatemala

By Alicia Robinson, ’11 (International Relations)

I came to Stanford after spending most of my life living in Guatemala, where my mother worked for the United Nations. As an international relations major, my focus was on human rights and international law. As a sophomore, I obtained the Stanford Human Rights fellowship to work for UNICEF in Cairo. I was a member of the Stanford Rotaract Club, where I organized a service trip to Guatemala and also co-founded the Central American Students Association to raise awareness on campus about the socio-political realities of this region. I subsequently pursued my JD at Harvard Law School, where I continued to study human rights and post-conflict peace-building. I decided to return to Guatemala to contribute to efforts to curtail impunity, which has severely affected the country’s overall stability in recent years.

“The arc of the moral universe…”

By Oscar Sarabia Roman, ’17 (Public Policy)

Soon after starting my Public Interest Law Fellowship at the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project (IRP), I realized that impact litigation work is a slow process. The process focuses on big-picture outcomes and involves loads of abstract legal theory that apply to cases that may take years or decades to resolve. However, the attorneys never lost sight of how their work and, by extension, my work as an intern, contributed to the ultimate goal of achieving justice.

I was inspired and uplifted by all of the progress made by the ACLU IRP and by the ongoing battles these passionate attorneys are still pursuing. While it is easy to get lost in the legal proceedings, they never lost sight of the individuals they were helping and of the grand scale of their project. They never lost touch with their humanity or with the larger purpose and made sure I never did either. Their commitment reflects the famous quote by Martin Luther King Jr. who once said that, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Watching these professionals strive to increase civil liberties and immigrant rights has convinced me that this statement is absolutely true.

Oscar is a 2016-17 fellowships peer advisor.