Category: Health

Unequal Treatment: Exploring Unconscious Bias in Health Care

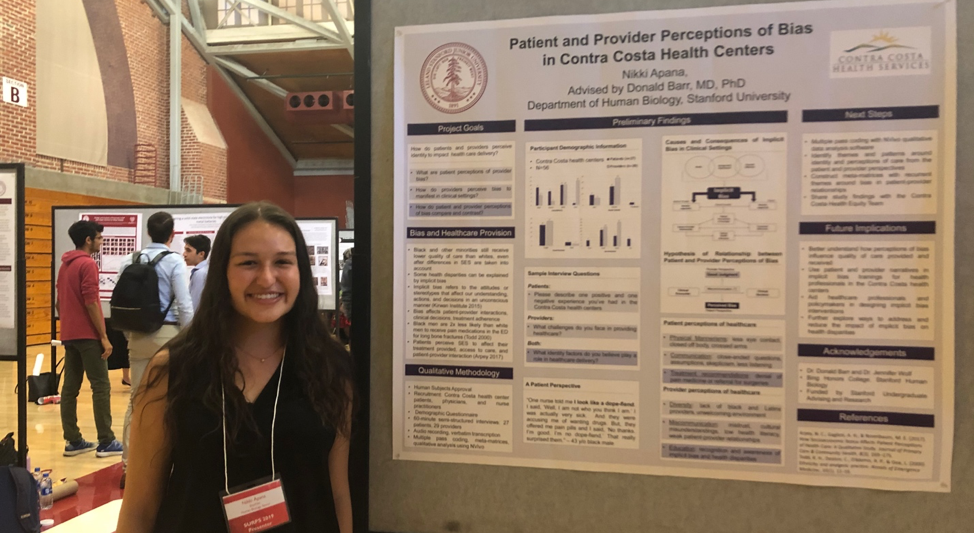

By Nikki Apana, ’20

“One nurse told me I look like a dope fiend. I said, ‘Well, I am not who you think I am.’ I was actually very sick.… And they were accusing me of wanting drugs.” – James (pseudonym), 43-year-old Black male

James is a participant in the community-based research project I have been conducting over the past three summers. I have been collaborating with Contra Costa Health Services, the public health system in my hometown, to find ways to address unconscious bias in patient care. Unconscious bias refers to the stereotypes we internalize that affect our behavior, judgments, and actions without our conscious awareness. And what is so pernicious about unconscious bias is that everyone has it, yet few realize it.

Unconscious bias covertly plays out in our everyday lives. As described in Howard Ross’s Everyday Bias, NBA referees call more fouls against Black players than White players, famous Black actor Danny Glover reported struggling to hail a New York City cab after dark, and job applicants with “Black” names are less likely to receive a callback than applicants with “White” names. Bias extends beyond race to gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, age, and weight. It surrounds us every day and it is embedded in our subconscious. Even when we think we treat everyone equally, pride ourselves on promoting equality, and call ourselves feminists, queer allies, and social justice activists, unconscious bias still pervades our minds and actions.

Bias is particularly injurious in the provision of health care. Even after differences in socioeconomic status are taken into account, Blacks and other minorities still receive lower quality of care than Whites. Innumerable studies in the American Journal of Public Health and Annals of Emergency Medicine show how bias can impact clinical decisions. Physicians tend to rate their Black patients as less intelligent, more likely to abuse drugs and be non-compliant with treatment, and less likely to desire an active lifestyle and have adequate social support. Minority children with accidental injuries are three times more likely to be reported for suspected child abuse than their White counterparts. Additionally, Black and Hispanic patients are two times less likely to receive pain medication in the emergency department than White patients.

James shared a similar account of being accused of seeking drugs and being denied pain medicine while seeking emergency treatment for a liver condition. His narrative is just one of many that I collected through the community-based research project.

This project grew out of a community need to address unconscious bias. During my first summer as a Community-Based Research Fellow through the Haas Center, I helped the Contra Costa Health Equity Team develop an unconscious bias training curriculum for health-care providers. The training has been piloted with over 500 providers and continues to raise awareness about the detrimental effects of provider bias. However, many participants have still expressed concerns about learning how to mitigate their bias in the clinical setting. I consulted with members of the Health Equity Team, and together we developed the next stage of research: interviewing patients and providers about their perceptions of unconscious bias in the health centers. This study seeks to center the voices of populations that have been historically marginalized and silenced. It will also identify concrete examples of insensitive behaviors in order to offer providers specific tools for reducing unconscious bias. I have already conducted 56 interviews with patients and providers, including the one with James, and have been qualitatively analyzing these transcripts over the last two quarters with the support of the Haas Center Public Service Scholars Program and my honors thesis advisors, Donald Barr and Jennifer Wolf. In the spring quarter, I will finish writing my honors thesis and deliver a presentation and report to Contra Costa Health Services with suggestions for improving the implicit bias training.

Community-based research has taught me the value of placing community needs at the forefront of identifying problems and enacting change. More specifically, this project with Contra Costa Health Services has given me the opportunity to explore unconscious bias in medicine, as well as my own unconscious bias. I am slowly becoming more aware of my own biases and more capable of stopping biased thoughts in their tracks. All the stereotypes we have learned can be unlearned once we recognize the ways in which we hold biases, foster dialogue about unconscious bias, and continue to acknowledge privilege and self-reflect on our actions and attitudes. Biases can be broken. With time and effort, injustices like those James has faced will become the exception rather than the norm.

You can find out more about your unconscious mind and take an Implicit Association Test (IAT) at Harvard’s Project Implicit.

Nikki Apana, ’20, studies Human Biology with a concentration in race, ethnicity, social class, and public health, and a minor in Spanish. Originally from Concord, California, Nikki has spent the last three summers in her hometown working as a Community-Based Research Fellow through Cardinal Quarter on issues of bias in the health-care system. At Stanford, Nikki serves as the lead Cardinal Service Peer Advisor, president of the Polynesian dance team Kaorihiva, and residential assistant in Branner Hall. Nikki has also worked as a SHAR(ED) volunteer throughout her Stanford career, was a Branner Hall Service Scholar, serves as a Cardinal Free Clinics Patient Health Advocate, and is a member of the Public Service Scholars Program.

Serving Those Who Have Served: 25 Years of United Students for Veterans’ Health

By Erika DePalatis, ’19

It all began in 1994.

While volunteering in the Alzheimer’s Ward of the Palo Alto Veterans Affairs Administration Hospital, Vance Vanier, a Stanford undergraduate studying economics and political science, noticed that many of the patients were suffering from loneliness.

With little connection to the outside world, many of these veterans rarely had the opportunity to interact with others, outside occasional family visits and planned events. Worse still, patients in this long-term care ward often experienced cognitive impairments such as Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia, which can make patients feel confused or distressed when isolated.

These veterans had served their community; Vanier wanted to help organize their community to serve them. Rallying forty other volunteers, Vanier founded United Students for Veterans’ Health (USVH) with the goal of building caring, meaningful relationships between students and long-term care patients in Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospitals. Vanier’s brother, Andre, launched USVH’s national expansion the following quarter and thereafter expanded his role as the chair of USVH’s National Advisory Board.

Over the years, USVH has expanded across the United States, becoming one of the first nationwide student organizations connecting students with hospitalized veterans. Chapters at the University of Southern California and University of Alabama were founded several years ago, and the group’s sustained growth still continues: earlier this year, a new USVH chapter was established at the University of San Francisco, supported by the diligent efforts of USVH’s national co-presidents, Stanford students Komal Kumar, ’20, and Zane Norville, ’21.

“Our chapter in San Francisco has been a long time coming. The veteran population at the SFVA hospital is conveniently located near two undergraduate universities, San Francisco State University and the University of San Francisco. …[W]e are proud to say the program is launching now, with a group of six dedicated pilot student volunteers,” explains Kumar.

The original Stanford chapter of USVH, however, has never forgotten the local need which first started this national organization. Each fall, USVH recruits new volunteers to serve veterans at the Menlo Park Veterans Affairs Hospital (MPVA). Student volunteers visit the hospital’s long term care facility, where many of the veterans have been living for several years, and, through weekly visits, build meaningful friendships. The group’s connection with the local veteran community has only grown during its many years of operation, as evidenced by the group hosting an increasing number of events at the hospital each quarter, including an event this past fall that attracted the highest veteran turnout in USVH’s history, with over 25 veterans in attendance.

“The hospital can be a dismal and lonely place for some of the veterans,” explains USVH alumni John Rodgers, ’19. “Although it could feel like a small thing to visit the VA once a week, listening to someone’s story and really trying to get to know them can go a long way toward improving their time in the hospital.”

In addition to the relationships built between USVH participants and veterans, USVH plays an important role on campus by hosting educational events that inform the campus community about issues affecting veterans. For example, USVH partnered with the Stanford United Veterans Association (SUVA) in October 2019 to host two SUVA representatives and a VA psychiatrist for a panel discussion on veterans’ portrayal in the media.

This year, USVH celebrates its 25th year of partnership with the Haas Center for Public Service, during which time USVH volunteers have reported serving over 50,000 hours at the MPVA. In partnership with the Haas Center, USVH honors students who sustain their involvement with the group for at least three quarters by offering them a Cardinal Commitment certification. Since the launch of the Cardinal Commitment program just two years ago, 16 USVH students have received this certificate.

The thought of over-scheduled Stanford students consistently making time each week to visit elderly veterans might strike some as surprising; but Kelly Beck-Sordi, Haas Center Associate Director and Director of Cardinal Commitment, would explain that, instead, the dedication of USVH student volunteers is just one example of the growing culture of service on campus.

“Every year, hundreds of Stanford students make year-long commitments to serve with student groups, community organizations, and campus programs, from teaching local youth how to code to advocating for workers’ rights,” Beck-Sordi explains. “USVH has been very successful in engaging students over the years, and that’s because students care about serving those who have served our country. Students want to give back.”

Erika DePalatis, ’19, serves as the Communications Coordinator at the Haas Center for Public Service. Prior to her work at Haas, Erika studied English and Italian at Stanford and worked as an oral communications tutor at the Hume Center for Writing and Speaking. Her role allows her to elevate student stories of service and connect Stanford students with service opportunities.

Hidden in Plain Sight: Deconstructing the Mental Health Stigma

By Anika Sinha, ’21

Content Warning: This post contains information related to self harm and mental illness that can be difficult to review. Please make use of campus resources such as Vaden Health Center’s Counseling & Psychological Services and The Bridge Peer Counseling Center to support your safety and well-being.

“I cut myself pretty often. I want to stop but I can’t. How do you stop?” My teaching partner and I stared at this card for longer than usual, then glanced at each other, unsure of how to proceed.

I am a classroom teacher for Health Education for Life, Partnerships for Kids (HELP4Kids). Every Friday, I teach health education to sixth graders at a local middle school. Topics include mental health and wellness, exercise, nutrition, drugs and alcohol, and sleep. Most of my days in the classroom are full of giggles and interrogations about the college experience. Questions can range from: “What classes are you taking?” to “How often do people get drunk?” HELP4Kids lets me escape the Stanford bubble for a brief hour and immerse myself in the colorful world of a middle school classroom. Regardless of my mood on campus, I trust the kids to bring a smile to my face… but this is not always the reality.

At the end of every class, we hand out notecards to the students, so they can ask anonymously any questions they may be uncomfortable to ask in front of the class. The topics we discuss can be quite sensitive and personal, so we want to give space for deeper discussions. Some of the notecards are random sketches pulled out of wild 11-year-old imaginations, some are simple “thank you’s,” and some even contain memes. However, the majority include thoughtful comments or questions about the day’s lesson.

The day we taught a lesson about mental health, I knew we would receive some sensitive questions. But I was still stunned and unprepared to find out that one of my students was struggling so deeply. This indicated my own naiveté. How could someone so young be afflicted to the point of hurting themselves? I thought. After reflecting for a while, I realized that this very mindset was part of the problem. Instead of marveling at how problems like this could even exist, I needed to consider the underlying systemic issues perpetuating my surprise. This child had obviously been hiding this issue. Without the notecards we passed out, they would not have had a platform to speak up. Their reluctance to ask for help ultimately boils down to the stigma attached to mental health issues, a problem that ravages our society.

After reading the notecard, my co-teacher and I reached out to the classroom teacher and school nurse immediately to address the situation. They informed us that they knew the student who wrote the note, and would follow up imminently to ensure they received proper care.

Experiences like this one have shown me that reducing stigma around mental illness is of paramount importance, especially when it comes to adolescents. More notecards from the students in HELP4Kids revealed similar themes, and those were just from the ones who were brave enough to speak up.

I know I am just barely scratching the surface of this issue, but I am doing what I can to reduce this stigma on campus. As a residential assistant and co-president of Stanford Mental Health Outreach, I have been committed to normalizing conversations about mental illness through speaker panels, mental health short films, and fostering vulnerability with my residents. The more these conversations occur, the more students will be able to admit to themselves and to others that they are struggling. This is the first step toward healthily managing life with a mental illness.

My experiences are teaching me that mental illness is relentless: nobody—no matter their age, gender, career, income, education—is given a free pass. If someone seems too young or too accomplished to be battling with it internally, I need to think again. To combat stigma, we need to foster platforms where people can speak openly about their struggles, without fear of judgement… and, most importantly, with the promise of support.

Anika Sinha, ’21, is majoring in human biology with a minor in psychology. In addition to working with youth through HELP4Kids and Peer Health Exchange, Anika is involved in Student Clinical Opportunities for Premedical Experience (SCOPE) and Stanford Mental Health Outreach (SMHO). You can find Anika at Branner Hall as a resident assistant, or at the Haas Center for Public Service, where she serves as a Cardinal Service Peer Advisor.

Beyond the Stethoscope: Addressing the Social Determinants of Health

By Nikki Apana, ’20

For my uncle, no level of mental health treatment could cure his chronic homelessness. No number of visits to the psychiatrist could shield him from the physical and psychological trauma that accompany living on the street. Having witnessed the effects of homelessness on my uncle’s overall wellbeing, I became deeply committed to addressing healthcare disparities through medicine and public health.

At Stanford, I sought out courses that could help me understand my uncle’s experience and how to help. My frosh year I found a Cardinal Course that allowed me to combine my academic interests in public health and passion for public service: Social Emergency Medicine and Community Engagement. In the class, we discussed how socioeconomic status affects health status, and I got to see how these trends play out in the emergency room (ER) through a partnership with our partner organization, Stanford Health Advocacy and Research in the Emergency Department, or SHAR(ED).

The emergency room is a safety net. When people don’t have anywhere else to go, that’s where they end up. Sometimes emergency room patients come in for something as minor as a cold—or a serious condition after a minor condition goes unmanaged for a long time. The hospital ranks the severity of a patient’s condition on a scale of one to five, with one being the most severe. But the ranking says little about the social causes of their illness.

As a volunteer, I screened patients at the Stanford Hospital Emergency Department for social needs that could negatively affect their health. Some of the most common issues included the lack of affordable housing, difficulty accessing a primary care physician, high cost of childcare, lack of healthy food, and difficulty paying utility bills. At the end of each visit, I referred patients to local organizations to help reduce the burden of these needs on their overall health.

I valued providing patients with resources to help them cope with different pressures and reduce the frequency of their visits to the emergency room. However, in medicine there is still a disconnect between physicians and patients: ER physicians are there to only treat serious medical conditions, while patients want any treatment.

During one of my volunteer shifts, I was with a Spanish-speaking patient and a nurse asked if I spoke Spanish. I nodded.

“Oh great! Can you translate for me?” the nurse asked. Then she quickly rattled off a number of test results to me. “Her CT scans, blood test, and everything else look normal. Can you tell the patient that everything is fine and that she should just go see her primary care physician?”

I did as the nurse said. Then, the patient looked at me and asked, “Are you sure there’s nothing wrong?”

From an operational standpoint, the nurse was right; the patient should have gone to a primary care physician instead of the ER. But this patient was like many others in the ER who have never heard of a primary care physician or simply cannot afford it.

As I learned from a young age, addressing medical issues requires so much more than scrutinizing physiological symptoms and abnormalities. Access to healthy food, affordable housing, and high-quality healthcare all contribute to individual health and wellbeing and can prevent frequent visits to the emergency department.

After taking this Cardinal Course, I pursued honors thesis research on the barriers patients face in seeking healthcare—research that I plan to use to advocate for policies that ensure patients’ basic right to high-quality healthcare.

As I look beyond graduation, I hope to apply to medical school and become a primary care physician, with the knowledge that a state of complete health cannot be achieved without remediating the underlying social challenges that patients face everyday.

Nikki Apana, ’20, is a premed student studying human biology, with a concentration in race, ethnicity, social class, and public health. She is a Cardinal Service Peer Advisor, Community-Based Research Fellow, volunteer with SHAR(ED) and, patient health advocate with Cardinal Free Clinics. She is also involved with Kaorihiva, the Polynesian dance group at Stanford. Nikki is from Concord, CA.

Music, Laughter, and Joy: A Summer of Therapeutic Music in Senior Living Communities

By Samantha Starkey, ’19

Research shows that singing has beneficial effects on the mood, cognition, and health of older adults. These findings are the basis of my placement organization last summer, SingFit, a Los Angeles-based startup that uses technology to make therapeutic music more widely accessible for older adults. During my time interning with SingFit, I saw how one-on-one and group therapeutic music sessions in senior living communities enhance the well-being and social engagement of older adults.

At one of my group sessions at a memory care facility, there was a gentleman who at first seemed confused and disgruntled.

“I can’t sing. I don’t know the words. I can’t even hear properly,” he complained.

As time went on, he began singing along with the group, and he would suggest songs from musicals like West Side Story, once gracing us with a brief rendition of “Maria” in a mellifluous tenor voice.

One day, we sang the Andrews Sisters song, “Beer Barrel Polka.” Most songs have associated dance moves to encourage movement, and we all repeated the “Beer Barrel Polka” move throughout the song: pretending to drink a mug of beer. Afterward, with a deadpan face, he looked at me and mock-sternly cried, “You’re over your limit!” The whole group giggled.

That gentleman was just one of the many people who had a profound impact on me this summer. Working with him made me realize that patience, respect, and music can bring out talents, humor, and joy in people.

Sam Starkey is a senior studying human biology and education. Samantha served as a Roland Longevity Fellow with SingFit. At Stanford, she has been involved in several Cardinal Commitment student organizations, including Side by Side, The Bridge, and Ravenswood Reads. She is from Vancouver, Canada.

Advocating for patients and policy change

By Brian Kaplun, ’18 (Human Biology), MS ’18 (Management Science & Engineering)

I’ve wanted to be a doctor ever since I was a kid, but it was an experience as a research assistant at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles right before coming to Stanford that showed me there is more to healthcare than a doctor’s visit. There, I met a small boy who had gone blind due to his family’s lack of consistent access to healthcare—an entirely preventable loss. Based on this experience, and the many lessons on injustice and inequity to come, my coursework, advocacy, and service over the last four years have all been part of a deeply held commitment to addressing healthcare disparities.

I started volunteering at the student-run Arbor Free Clinic my first quarter at Stanford as a Bridge to Care counselor. It was my job to find patients what the clinic couldn’t provide—from health insurance and a regular doctor to temporary housing, legal assistance, and job training. I learned how a difficult diagnosis or untreated illness could impact every aspect of one’s life, and about the potentially harmful interplay between health and sociopolitical factors—including from far too many undocumented families scared to seek healthcare out of fear of being separated and torn apart.

This was—and still is—the hardest job I’ve ever had, but it was the first time I felt like I had the knowledge base to help others. However, even after three years on the team, the sheer complexity and gaps in the healthcare system and the broader safety net meant that often our patients couldn’t get the help they needed.

I worked my way up to become clinic manager, overseeing more than 100 undergraduate and medical student volunteers. As the primary liaison to other Bay Area community health centers and agencies, I worked to strengthen collaborations to provide patient resources, including up-to-date information on topics such as immigration assistance, domestic violence resources, and pro-bono surgery options. Most importantly, in my successes and failures as a volunteer and manager, I learned that as an outsider to the communities we served, I needed to recognize my privileges and biases; the most important thing I could do was know when to listen, and to stay humble and empathetic.

As a gay man, I have struggled with less-than-inclusive care, and LGBTQ+ advocacy has been an important part of my passion for healthcare equity.

At Arbor Free Clinic, I co-led the Queer Health Initiative, a multi-year project to systematically improve services and care for LGBTQ+ people. I also served with the Human Rights Campaign on the Healthcare Equality Index, a tool focusing on inclusive hospital policies, and at Pangaea Global AIDS as a Huffington Pride Cardinal Quarter Fellow, studying the HIV policy landscape for gay men and trans women in Zimbabwe.

While one-on-one patient interactions reaffirmed my goal to be a physician, through Stanford courses on racial and ethnic health disparities, the American healthcare system, and policy analysis, I learned about the broader policy and social landscape that leaves so many patients behind. Last summer, as a Sand Hill Foundation Cardinal Quarter Fellow at Kaiser Family Foundation, I applied this learning to writing policy analysis and issue briefs about changes to the Affordable Care Act and the state of the HIV epidemic for gay and bisexual men.

In the coming year, as a 2018 John Gardner Public Service Fellow, I will staff the Democratic health policy team for the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee in the U.S. Senate, with Deputy Health Policy Director Andi Fristedt as my mentor. This committee is the battleground for many of the fights over Affordable Care Act repeal, healthcare costs, and reproductive justice, and where legislation to curb the opioid epidemic is taking shape, and I’m excited to dive into these important efforts. Following the fellowship, I will pursue a medical degree at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

At Stanford it was service that affirmed, over and over, the issues I cared about and the ways I needed to be involved. Through my Cardinal Commitment, I learned how to channel my frustration with inequity into a constructive desire to do more. As I look toward life after Stanford, I hope to continue working in both the clinical and systemic aspects of health—as a doctor healing individual patients, and as a policymaker and advocate working on the broader factors that affect their wellbeing.

Brian Kaplun was one of more than 300 students who declared a Cardinal Commitment in 2017–18.

Seeing the invisible

By Jenn Ampey, ’19 (International Relations)

The last strand of decorative lights fell into place as the clock struck 7:00 pm. After more than nine months of hard work, it was time to open the doors to “Kaleidoscope: Mental Health Coming into Focus.”

As students filed in, I couldn’t help but stare in awe at the number of students that had come to immerse themselves in the mental health experiences of their peers through art. Many visiting students stayed for upwards of an hour. As co-president of Stanford Mental Health Outreach, I have long had the privilege of engaging with students and faculty across campus on mental health issues. However, the art showcase was a new venture. It involved more than 60 non-members, including student artists and the students photographed. Without them, SMHO would not have been able to host such a moving gallery.

We need to continue to have provocative interactions around mental health issues. Doing so with different media is one more way to reach out to our peers and offer our experiences in an effort to destigmatize conversations that could make an enduring difference in someone’s life.

As the event drew to a close, surrounded by artistic expressions of sometimes indescribable human experiences, my co-president and I found comfort in the realization that we helped build bridges—bridges that we hope will be crossed again and again at Stanford going forward.

Jenn was a Peer Advisor at the Haas Center in 2017-18, in addition to her work with SMHO.

Know history, know self, know mental health

By Joriene Mercado, ’18 (Human Biology, Education)

I was back in a high school classroom in my hometown of Daly City, California, to facilitate a workshop for nine students about Filipino history, mental health, and ethnic identity. As I was leaving, one of the students said that during this workshop they learned about history in a way that they hadn’t in an entire semester of their history class.

Throughout high school, I never had the opportunity to learn about or discuss Filipino history; I first learned about it through a student-initiated course at Stanford. And it wasn’t until college, once I began to struggle with my mental health, that I took the time to even consider mental health. When I saw how the two intersected and influenced my ethnic identity development, I felt I would’ve been much better off if I had learned about mental health and my Filipino history in high school. However, I’ve been privileged to attend Stanford, and I hope to help high school students in my community by sharing what I’ve been fortunate to learn about.

In the future, I want to continue teaching our youth and ensuring that they can see themselves in what they’re learning. Knowing one’s ethnic history is critical for positive and complete identity development, especially during high school.

“Know history, know self. No history, no self.”

Joriene is a member of the 2017-18 cohort of the Public Service Honor Society.

Learning about my communities

By Vanuyen Pham, ’18 (History)

“Why is sexual and reproductive health important to you?” I asked a student.

I’m back in high school for the day. As part of my summer internship with Southeast Asia Resource Action Center (SEARAC), I drove down from our offices in Sacramento to interview Southeast Asian American youth in Oakland about their access to sexual and reproductive health services.

The students described the difficulty they face around accessing services and products because of cost, on top of the cultural stereotyping that happens in neighborhoods where some of them live. The students were far more knowledgeable about the complexity of sexual and gender identity than I was when I was their age, and understood how fortunate they were that they went to a school with a clinic that provided what they needed.

This was just part of my summer at SEARAC, where I had an amazing and fulfilling experience through the Empowering Asian/Asian American Communities Fellowship. I outreached to congressional offices, followed the latest updates on the federal efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, contributed to reports on the impact of the ACA and inter-generational trauma on Southeast Asian American communities, and participated in legislative visits to the State Capitol. Through my experiences, I gained a better understanding of the power of community organizing and policy change and am passionate about pursuing postgrad opportunities in public health and public policy to advocate for my communities.

Vanuyen is a member of the 2017-18 cohort of the Public Service Honor Society.

Heart in service

By Melodyanne Cheng, ’18 (Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity and Biology), MA ’19 (Comparative Medicine)

“I carry my community on my back,” said the man who stood tall at the front of the East Palo Alto City Council meeting room. He was dressed in vivid ink tattoos and wringing a beanie between his hands. He proclaimed himself an elementary school graduate, and the observing crowd fell palpably silent. When the city council questioned his qualifications, revealing his lack of skill and experience for the position in comparison with the real estate lawyer candidate and the previous board member running for re-election, the man proudly defended his right for candidacy on the Rent Stabilization Board as a proud product of East Palo Alto. “I may not have training,” he boomed, “but I have heart.”

As a Community Health Advocacy Fellow, I was an outsider observing the rent control committee elections, hoping to understand some of the political events that have great impact upon the overall health of the community I served. Unlivable conditions, lack of accessible housing, rocketing rent prices, and gentrification are negatively affecting the East Palo Alto community and the health of the patients I serve.

The man’s words echo in my mind as I volunteer at Ravenswood Family Health Clinic, which serves a patient community that is majority low-income. It’s been my absolute joy to get to know patients as they share precious pieces of their life stories with me. As I interact with patients as a women’s health navigator, I see patient wellness impacted by so many different upstream social determinants of health, such as zoning policies, housing affordability, and housing conditions. I’m honored to serve these amazing people in whatever capacity I can, now as a patient advocate and in the future as a community health-focused physician.

Melodyanne is a member of the 2017-18 cohort of the Public Service Honor Society.