Category: Environmental Sustainability

Flying Solo at the Santa Lucia Conservancy

By Max Klotz, ’20

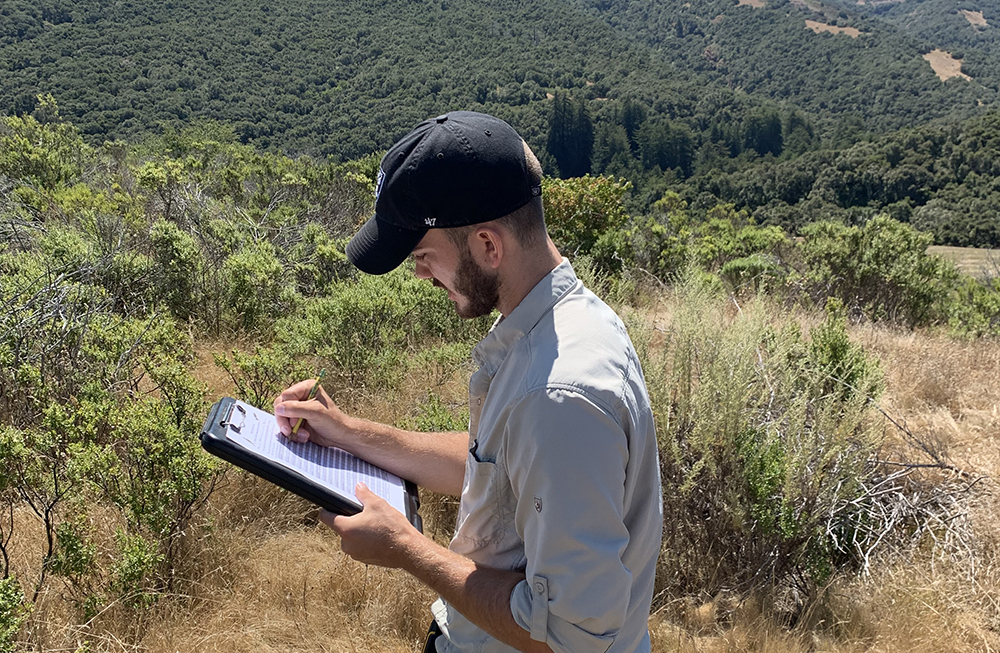

When I made it to the trailhead, Hall’s Ridge was still blanketed in mist. I couldn’t see 15 feet from me, let alone the views down into the valleys on either side of the ridge. I used the delay to organize my photos and make sure I knew the location of each photo point, places with distinctive landmarks that could provide a record for evaluating vegetation changes over time.

The morning mist quickly gave way to sun as, seemingly in minutes, the fog layer around me burned off to reveal views all the way to Monterey Bay. Now having the visibility necessary to capture my photographs, I set off on the trail. I spent the rest of the day hiking and taking pictures, not just of my photo points, but also of the hawks and vultures that circled by the trail.

My project at the Santa Lucia Conservancy in Carmel consisted of selecting and replicating historical photographs of the Santa Lucia Preserve to show the land’s changes over time as part of broader ecological conservation efforts. The process for obtaining repeat photographs of each historical picture was intricate. First, I had to carefully select historical photographs that featured distinctive landmarks in the preserve. Then I worked with my supervisor to identify the approximate locations of each historic photo point and map them using waypoints on the MapItFast software. Finding the exact location for each historical photograph and taking current pictures with the same framing were the final and most challenging steps. I had been struck by the beauty of some of the historical photographs on Hall’s Ridge, so I was excited to explore the area. Early on in my internship at the Santa Lucia Conservancy, I had mostly explored the preserve with other employees, but as my project progressed, I came to enjoy the meditative nature of the days I spent on my own. I set out in a company truck with my water, lunch, camera, and stack of historical photographs. Several weeks into my project, I began to make my way around the different photo locations on the preserve to capture what those photo points look like now. In the process of driving and hiking from place to place in search of historic photo locations, I started to become familiar with the land and its intricacies.

As I looked at my photographs at the end of the summer, I realized the project had shown intriguing results. There had been dramatic changes in some areas of the preserve and a dramatic lack of change in others. Through photography, I was able to track brush encroachment on grasslands, lands recovering from fire treatment, and other broad changes over the course of decades.

This hands-on Cardinal Quarter experience has given me an understanding of the power of combining ecological studies with creative work, as well as a desire to continue to use these tools throughout my career.

Originally from Stanford, CA, Max Klotz, ’20, studies human biology with a concentration in environmental studies. Max completed a Cardinal Quarter during the summer of 2019 with the Santa Lucia Conservancy in Carmel, CA. In addition to engaging in a range of hands-on conservation activities, he helped develop a project to reproduce historical photographs of the Santa Lucia Preserve in order to document environmental change over time. View his “Repeat Photography” project on the Santa Lucia Conservancy website.

Girls Run the World in Gorongosa National Park

By Eric Wilburn, MS ’18, MA ’18

Gabriela “Gaby” Curtiz grew up just down the road from Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique. The park is one of the most biodiverse places on Earth and is surrounded by more than 200,000 people who live on very limited resources. These neighboring communities struggle to make ends meet due to lack of employment. Many young women in these communities lack the opportunity to finish primary school because of societal expectations, household responsibilities, and a shortage of schools and teachers.

When Gaby was twelve years old, her primary school showed a National Geographic film about Gorongosa National Park, sparking her dream to work with animals in the park. Nine years later, Gaby was certified as the first female safari tourism guide in Gorongosa’s history.

I met Gaby last year on her first trip to the United States. She was visiting Boise State University, where she will begin her undergraduate studies this fall. Of course, service was a part of her trip! She gave a talk to a group of elementary school students about Gorongosa. It was amazing to see their eyes light up and their hands skyrocket to the ceiling with questions about her life in Gorongosa. She emphasized the importance of working with local communities in conservation efforts, and explained that providing livelihoods for local families was the key to sustainable nature conservation. Her example? Coffee.

Why coffee? Because there are hundreds of families like Gaby’s living on the flanks of Mount Gorongosa that need an alternative to unsustainable agricultural practices to feed their families. There is no need for farmers to cut down the forests to make room for non-native crops, as farmers can plant native hardwood saplings in between the rows of coffee to provide shade. Coffee gives these farmers a dependable income while helping restore the rainforests of Gorongosa.

I was thrilled to hear Gaby share her story, and was particularly excited when she chose coffee as her example. Having recently graduated from Stanford, I had just begun working with Gorongosa National Park to launch Gorongosa Coffee, a for-profit company that sells premium roasted coffee around the world and sends 100% of profits back to the park to support operating costs.

After her talk, Gaby and I were chatting about how Gorongosa Coffee wanted each of our roasted coffees to support a different initiative in the park. Gaby said that the most unique aspect of Gorongosa is that the park fundamentally believes that girls’ education is the key to both human development and nature conservation.

Inspired by Gaby, Gorongosa Coffee created a Girls Run the World coffee that sends 100% of profits to help over 20,000 girls in Gorongosa finish high school. The funds help build schools, provide high school scholarships, and connect girls with mentors through afterschool programs. We hope to demonstrate that when we give girls in Mozambique the confidence, capability, and opportunities to determine their own futures, we encourage more leaders like Gaby.

One of the defining aspects of our model that helps ensure our company has a positive impact is that the lone shareholder of Gorongosa Coffee is the trust that funds the park. In other words, Gorongosa Coffee is a social enterprise which keeps control of this community-based initiative within the community it serves.

Gaby graduated from high school in Gorongosa and will start at Boise State University in September, pursuing a degree in business tourism. Her goal is eventually to become the head of tourism for Gorongosa National Park.

Gaby and I come from very different backgrounds, but we share a commitment to serving the people, wildlife, and ecosystems of Gorongosa. We believe that the path forward for people and the planet is that every business thrives, not to fill the pockets of a few shareholders, but in service of an equitable and sustainable future for all.

I invite you to help us empower young women like Gaby from the communities of Gorongosa to break barriers and bring positive change to their communities. You may order our coffee at GorongosaCoffee.com.

Eric Wilburn, MS ’18, MA ’18, served in the Peace Corps in Mozambique before arriving at Stanford to pursue dual masters degrees in environmental engineering and public policy. During his time at Stanford, Eric was a Graduate Public Service Fellow and also coached the Stanford Triathlon Team. Recently, Eric has been helping to launch a company called Gorongosa Coffee that aims to benefit local communities, wildlife, and nature in Mozambique by supporting conservation, education, and economic development.

Global Engagement: Engineering Solutions for Sustainability

By Adam Nayak, ’22

Ever since I was little, I have been fascinated with water. I grew up four blocks from Johnson Creek, a local stream in southeast Portland, Oregon. My mom took me down to the park to play in the water, letting the currents wrap around my legs as I searched for tadpoles and capered with dragonflies.

Each month, my family would wake up early in the morning to work with our local watershed council, removing invasive species, planting native species, and picking up trash around the stream.

It was here that my younger sister and I learned about the great salmon migration. I remember being fascinated with the fish: their perseverance, determination, and tenacity, traversing upstream to their birthplace to continue their lineage. As a boy, I was always searching for salmon, but as an urban stream, Johnson Creek faced serious water-quality challenges due to a history of pollution, and I was never able to find any fish.

As I grew older, I developed an interest in the science behind water treatment and ecological systems, looking for solutions to problems of contaminated stormwater and habitat loss. Volunteering with the Johnson Creek Watershed Council was one of my most rewarding experiences, instilling in me a value for public service and community engagement that has grown with me at Stanford.

Through my involvement in Engineers for a Sustainable World (ESW), a Cardinal Commitment student organization, I have been able to pair my interest in environmental conservation with engineering practice. In particular, I worked on a small team of students during a two-quarter Cardinal Course to design and prototype sustainable infrastructure solutions in Chavín de Huántar, Perú, an archaeological site in the Andes Mountains. Through the Cardinal Quarter program, I traveled to Perú with my team this past summer to implement the project and promote cultural conservation.

Our green roofs and modular tensile structures were designed as a new approach to flood mitigation in a rural setting, with a focus on aesthetic integration of roofing structures at a culturally significant site. This opportunity not only strengthened my Spanish language and communication skills, it allowed me to collaborate with engineers and community members, as well as to learn about engineering practices in the context of a different culture and setting.

Service is powerful to me because it establishes a sense of community and belonging. As a student who is passionate about equity and inclusion, I hope to work on sustainability projects in diverse communities worldwide. The experience in Perú has enhanced my ability to collaborate on a team that spans cultural backgrounds and has reaffirmed my passion for public service projects.

Now as a sophomore, I co-lead international ESW projects focused on sustainable engineering and equitable development. They have brought me back to the theme of water, leading a project with community partners in Ghana focused on organic waste mitigation and water treatment through biochar production for carbon filtration.

For me, service involves building relationships and working collaboratively, whether internationally with an organization like el Ministerio del Cultura de Perú, or locally with the Johnson Creek Watershed Council. Both experiences involved a long-term commitment to addressing community needs. From these experiences, I have come to focus on promoting equitable access to resources for all communities, regardless of background. Looking forward, I hope to continue my work in sustainable development as an environmental engineer, focusing on clean water and equity practices in the public sector.

Adam Nayak, ’22, studies civil and environmental engineering. Originally from Portland, Oregon, Adam’s childhood interest in environmental sustainability has led him to pursue a Cardinal Quarter in Perú, enroll in Cardinal Courses, make a Cardinal Commitment with Engineers for a Sustainable World, and serve as a Cardinal Service peer advisor. Adam has also been involved in the Multiracial Identified Community at Stanford; Stanford Strategies for Ecology Education, Diversity, and Sustainability; Students for the Liberation of All People; and Students for a Sustainable Stanford.

$5 Shuttle Buses to the Airport

By Kelsie Wysong, ’20

I have the pretty unique experience of getting into Stanford off of the waitlist. I remember actually getting a call from my admissions officer, rather than just an email or a letter sent to my house. He spoke with me for almost two hours about whether I should give up my spot at another school in order to take one at Stanford. As a first generation, low income (FLI) student, one of my main concerns about Stanford was money. I remember asking him how most students get to and from the airport when flying home over the holidays.

“Well, I think most students just Uber,” he responded.

Growing up in Metro Detroit, I’d never considered Uber as a transportation option. Even if Uber was more widespread in the Bay Area, I didn’t trust a random stranger to drive me, nor did I have a credit card to open an account. Even then, it seemed to me that Stanford could do more to help its students with getting to and from home.

Stanford is situated almost equally between the San Francisco and San Jose airports. While students have the opportunity to choose between the airports to find the cheapest flights, having multiple departure points makes it much harder to coordinate rides with friends or dorm mates. As a result, students take thousands of costly and carbon-filled individual trips to the airports.

In the spring of 2019, seeing a need to provide students with a more sustainable solution, the Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU) teamed up with Students for a Sustainable Stanford (SSS) to provide $5 bus shuttles to the airports during spring break. They sold 76 tickets and about half of those students checked in. While the initial trial was small, students who took the shuttles reported satisfaction with the price and drop off points.

I joined the project shortly after the trial run, having been involved with various other sustainability projects on campus. In the fall, we decided to offer the shuttles again to take students to and from the airport for Thanksgiving break. This second iteration sold out. Of the 225 tickets sold, 81% of people actually rode the buses. For winter break, we added more seats on each bus, and even included an additional third day of shuttles. Again, we saw an 81% turn out rate of the 375 tickets we sold.

So far, our shuttle program has been a huge success on campus. Student reviews have been overwhelmingly positive. In addition, our bus shuttles saved students thousands of dollars in Uber rides and prevented over 2,000 lbs. of CO2 pollution. We are excited to continue to learn from the spring break shuttles planned for later this quarter.

This project has truly been one of the highlights of my Stanford career, as I am able to help meet the needs of both the FLI community and the sustainability community. I believe that most students are looking for ways to leave Stanford better than they found it, and this project is my chance at contributing to that dream. When the next person debating on whether or not to attend Stanford asks how they will be expected to travel to and from home, ASSU and SSS will be able to give a sustainable, inclusive answer that directly shows how Stanford students provide solutions for their peers.

Originally from Wayne, MI, Kelsie Wysong, ’20, studies bioengineering at Stanford. Outside of the classroom, Kelsie is the ASSU co-director for environmental justice and sustainability and a member of the Senior Class Cabinet. Through a partnership between the ASSU and Students for a Sustainable Stanford, Kelsie helps organize shuttles to take students to the airport over breaks in order to reduce carbon emissions and save money. They also serve as the vice president of TapTh@T, Stanford’s tap dance performance group.

Our Islands, Our Stories: Oral History and Community-Building in Southeast Alaska

By Regina Kong, ’22

We were inside Taiga’s fishing boat, docked at the back of the cove. I remember taking a deep breath before setting the voice recorder down on the wooden table. The boat swayed side to side with the afternoon currents. Behind Taiga, I could see thickets of salmonberries and wild blueberries. According to the locals, the dense vegetation sheltered bears that roamed the island. I began the interview by asking Taiga about his childhood, and from there, I followed him as he spoke about everything from commercial fishing to ecology to fatherhood. To this day, everything about that experience and that summer feels entirely surreal.

Taiga was one of 15 people I interviewed for an oral history project I conducted through an internship with the Inian Islands Institute, a nonprofit experiential field school in Southeast Alaska that engages students in climate advocacy and sustainability. I found Inian as if by fate. When I reached out to Inian’s director, Zach Brown, PhD ’14, a few months prior to the summer of 2019, I learned that they had wanted to do an oral history project for a while, but had never had the capacity to do so.

“Do you think you would like to do this?” Zach asked me during one of our initial phone calls.

“Absolutely,” I said.

From a young age, I have always loved stories, especially those involving multiple generations and cultures. When I began thinking about interning with Inian, I was halfway through my freshman year and already thinking deeply about what a true education meant and what forms of wisdom could be attained outside of the traditional classroom—questions that I discovered resonated with Inian’s own mission.

And that was how, not even a week after the last day of school, I found myself in the breathtaking Southeast Alaskan wilderness, surrounded by endless swathes of forest and ocean. For the rest of the summer, I traveled by boat or seaplane to various communities, collecting stories surrounding the island’s homestead, fondly known by local fishermen as the “Hobbit Hole.” My goal was to preserve important community narratives containing such rich anthropological, ecological, and cultural histories; in the process of doing so, I realized that I was also preserving something much deeper.

Oral histories are a methodology for recording and preserving information not found in written records. Because they are shaped by the contours of an individual’s experience and reflections, they allow for the unearthing of rich and often unexpected stories. While these interviews proved emotionally intense, they also taught me how to listen deeply, how to be fully present. I heard incredible stories and met the wisest and most generous people. Strangers like Taiga shared their homes and lives with me, and I will always be grateful for that. From the changing climate in Southeast Alaska to the area’s geologic history to diverse definitions of home, I found myself continually learning more about this unique community as well as discovering a greater human narrative of love, endurance, and connection.

I know this summer will continue to shape who I am for the rest of my life, and I hope to take these stories and gleams of wisdom with me wherever I am in the world. To Taiga and everyone else who made this experience as special as it was and continues to be, thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Regina Kong, ’22, is from Berkeley, California, and is currently studying comparative literature and art practice at Stanford. She spent the summer of 2019 gathering oral histories from locals in Southeast Alaska as part of the Donald Kennedy Summer Projects Cardinal Quarter fellowship with the Inian Islands Institute. At Stanford, Regina serves as a producer for the Stanford Storytelling Project and works as a student tour guide.

How an Urban Studies Class Made Me a Better Engineer

By Katherine Erdman, BS ’19, MS ’20

As the countdown to graduation began, I, like many other Stanford seniors, was eager to complete my general education Ways of Thinking/Ways of Doing. As I planned my fall quarter, I was on the hunt for a class that satisfied my last unfulfilled requirement: Engaging Diversity. There were almost 200 classes to choose from, but I settled on Urban Studies 164: Sustainable Cities. I had a mild interest in environmental technology, so I decided to give it a go.

On the first day of class, I was surprised that the focus of the course wasn’t on hydrogen fuel cells and electric cars. Rather, environmental health was just one of four aspects of sustainability we would be tackling, in addition to cultural continuity, social equity, and economic vitality. This broadened definition of sustainability, going beyond greenhouse gases and air quality indexes, was especially meaningful on the day we talked about transportation in the Bay Area. Like many other computer science students, I spent a summer interning at a large technology firm just miles from campus. I did not have a car and benefited from the shuttle service provided as part of the job. Every morning, I walked a few minutes to the nearest stop, hopped on the bus, and arrived to work without issue. I brought this up as an avenue to increase sustainability. The buses were quite full and eliminated at least hundreds, if not thousands, of mostly single-occupancy cars from the road. While my classmates agreed that the shuttles helped with environmental health, I was challenged to also consider the soaring housing prices near newly placed shuttle stops that make longtime residents unable to afford to stay. They are often replaced by tech workers, eager to be closer to the shuttle stop and able to afford higher rent. Perhaps certain shuttle stops trade off cultural continuity in pursuit of sustainability?

Through many eye-opening discussions, I more clearly saw the effects of sustainability efforts within the social and cultural realms by the end of the quarter. I walked away with a new perspective, which I applied to my senior project class CS210: Software Project Experience with Corporate Partners. My CS210 team partnered with Oracle and was given the task of creating social good technology. We decided to tackle the issue of employment opportunities for formerly incarcerated individuals. Within this space, it’s easy to identify unmet needs, such as the need for technological education for someone who has been disconnected from the job market for a number of years or the need for mock interviews for someone who has never formally applied for a job before. However, my experience in Urban Studies 164 helped me understand how any solution has to fit within a larger ecosystem. I found that my team and I were challenged to look beyond economic vitality and consider the cultural continuity and social equity concerns that our solution had to address. Whether integrating our solution into the parole preparation process for the incarcerated in Australia or modifying the product’s user interface to be approachable for first-time digital users, our team attempted to address cultural and social issues that appear tangential, but are deeply connected to the product’s success.

Katherine Erdman, BS ’19, is a coterminal master’s student in computer science from Ellicott City, Maryland. During her senior year, she took Urban Studies 164: Sustainable Cities, a Cardinal Course that introduces students to sustainability concepts and urban planning as a tool for determining sustainable outcomes in the Bay Area. Katherine has been involved in the Business Association of Stanford Entrepreneurial Students, SHIFT: Healthcare Innovation @ Stanford, and she++. She is also a member of the Student Alumni Council and the Viennese Ball Steering Committee.

The Global and Local Conversations About Agricultural Conservation

By Kyle Van Rensselaer, ’19, MA ’20

What happens when you pave over a garden? The consequences are fairly small. How about when unchecked urban development paves over tracts of fertile agricultural land?

In a state like California, a major breadbasket for the United States, such changes can threaten food security, land conservation, and farmer welfare. These are pressing issues that the California Department of Conservation’s Division of Land Resource Protection (DLRP) is aware of, and that I was able to help tackle during my Cardinal Quarter in summer 2018.

During my time as a fellow, one of my major assignments was a research project looking into unique agricultural policies in other countries, namely the Netherlands and Israel. My research contributed to a longer white paper that was presented at a UC Davis symposium on climate change in September 2018, which was itself affiliated with the well-known Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco.

The white paper discussed Californian agriculture broadly and paid particular attention to agricultural conservation in the face of climate change. The Netherlands and Israel, as I discovered through my research, are notable because they prioritize agricultural productivity and sustainability in their legal and economic structures, albeit in much different ways.

Despite having a high population density, the Netherlands has an incredibly efficient agricultural sector that invests in innovative practices such as urban rooftop gardens, large-scale greenhouses, and public engagement with sustainable farming. Israel, on the other hand, caught our attention because 93 percent of its agricultural lands are owned and leased out by the central government, creating an interesting dynamic between free-market impulses and traditional conceptions of how national land should be used.

Although reading about these international programs was fascinating in itself, my team and I were most interested in how the policy prescriptions in the Netherlands and Israel could be applied to California law.

In particular, DLRP is interested in expanding and improving its conservation easement program. This program is designed to promote agricultural conservation by bringing farm owners, land trusts, and the California state government together to protect private farmland from development into perpetuity. I was lucky to visit some of the farms that have signed conservation easement contracts and are therefore committed to conservation efforts on their own properties. These visits were a great learning experience because I was able to see how the Department of Conservation builds dialogue with key stakeholders: the farmers who keep California’s agriculture sector alive and running.

The partnership between DLRP and private landowners gave me insights about community engagement and cultivation. Despite political divides, the government and its stakeholders can find common ground and achieve mutually beneficial outcomes.

In particular, many farmers in California support the Republican Party and, as such, tend to be more skeptical of the environmental policies that lawmakers in Sacramento actively pursue. However, DLRP’s conservation easement program has generated buy-in among these farmers because all parties agree on the relevance of supporting agriculture in the long-term.

My research project seemed more relevant when considered alongside these takeaways from the field: while public ownership of farmland, as in Israel, would be a hard sell in the United States, the targeted investments into agricultural sustainability such as those that the Netherlands makes are much more palatable for farmers in the Californian Central Valley. Witnessing DLRP’s role as mediator between lofty policy goals and actual hands-on implementation of farmland conservation was an opportunity to see how the government can bring together diverse stakeholders, and even unusual allies, to preserve a way of life for generations.

Kyle Van Rensselaer, ’19, MA ’20, is an international relations major, chemistry minor, and coterminal student in international policy. He is the historian for the chemistry fraternity Alpha Chi Sigma, head writer for Stanford Chaparral Magazine, a peer chemistry tutor for the Vice Provost for Teaching and Learning, and a member of the Stanford Axe Committee. He is from Auburn, CA.

Notes from Magic Beach: small-town sustainability in southeast Alaska

By Madelyn Boslough, ’18 (Electrical Engineering)

Sea lions sang me to sleep in the dusky pink afterglow of a midnight sunset in southeast Alaska. Their bellows, echoing across the strait to my tent on Magic Beach, were surprisingly soothing, harmonizing with the gentle crash of tiny waves on gravel and kelp. The beach was aptly named. Each morning, I woke under a low ceiling of fog, obscuring the peaks of the Inian Islands and giving the whole place a mystical air.

Though I was born and raised in Alaska’s Wrangell St. Elias National Park, I had never spent time in the Southeast region of the state until I was awarded a Cardinal Quarter through the Alexander Tung Memorial Fellowship to serve with the Inian Islands Institute.

I was captivated by the beauty of the Institute’s location on a remote rainforest island off the coast of Gustavus, Alaska, and intrigued by its mission of inspiring youth to care about the environment by using experiential education. The Institute was founded by four Stanford PhD students, including the director, Zachary Brown, a recent PhD graduate in environmental science and fellow Alaskan.

The school intends to model sustainable living, and Zach offered me a position updating the Institute’s micro-hydroelectric system, which provided electricity to off-grid property. I was thrilled to take the lead on a project in small-scale renewable energy. I love Alaska with all my heart and have always intended to use my education to serve the environment and communities that shaped and supported me. I majored in electrical engineering to work in renewable energy and influence my state to rely less on oil and use more environmentally friendly technologies.

Over the course of the summer, I researched existing micro-hydroelectric systems in rural Alaska and began to plan a retrofit of the system on the island. I assessed the school’s present and future electricity demands, and the potential for incorporating other renewable energy sources like wind and tidal.

I was grateful for training in Stanford’s Principles of Ethical and Effective Service, especially preparation and humility. Preparation guided me through the tasks and challenges I expected; humility allowed me to navigate the inevitable unexpected tasks and challenges for which I had not prepared.

For example, on my first trip to the island where the Institute is based, I discovered that I would be closely working with a seasoned fisherman named Greg. Greg was a brilliant engineer without a college degree, who imagined, designed, and installed the micro-hydroelectric system on the island in the 1980s, long before terms like “renewables” and “microgrids” were heard in Alaska. He had done all this by corresponding with a Canadian hydroelectric manufacturer via handwritten letter, and with the help of a few good friends for the system’s actual construction.

Then, nearly 40 years of dependable renewable electricity later, I showed up to “fix” his ingenious but aging design. It took weeks for Greg to stop responding to my questions with a terse, “You’re the electrical engineer; you tell me.” Only by persistent, respectful questioning and listening was I able to earn his grudging willingness to help me.

Living in Gustavus was a profound civic awakening. An isolated town of only 400 people, Gustavus is an intimate place where everyone knows everyone, and every person plays a visible role in the social fabric. Just by arriving, I took on a role as well. My actions could affect everyone in town, and realizing this, everything I did took on a greater importance. I had a responsibility to the community of Gustavus, and by the end of the summer, I had made an impact. I left knowing that my actions make a difference and that I can be of real service to the Alaskan communities I love.

Working on small-scale renewable energy was a microcosm for the greater issues of climate change and planetary sustainability—a window into a wicked problem. Working with Zach, Greg, various handymen and community volunteers, and the Institute’s board of directors pushed me to understand how to work with a team with diverse expertise to tackle difficult problems. Through my fellowship I focused on the questions of what I want to do with my life and what kind of impact I hope to have on this world. I learned from Zach that a bias toward action is key—in the face of a terrifying, massive problem like climate change, the only thing to do is to choose somewhere to start, and do something.

Madelyn was one of 486 students who completed a Cardinal Quarter in 2017.

Building cultural sensitivity in conservation

Maria Doerr, ’17 (Environmental Systems Engineering)

When the rain starts, we’re not ready. Ten of us stand in the truck bed, grasping the railing as the vehicle lurches down the muddy trail. “¡Aquí!” our community partner Sapo (“toad” in English) yells, grinning while he pulls up a dusty plastic tarp from below our feet. We stretch it over our already-soaked heads as the truck continues weaving through the forest.

Since September, I’ve been working as the Water & Cities Fellow with Conservation International Mexico, supporting an initiative to protect the watersheds of Mexico City.

Mexico City’s water issues are complex. When it rains, parts of the city flood. Every day, approximately 1,000 people settle in the city, creating an ever-growing thirst to quench with an ever-dwindling water supply. The aquifers that provide 70% of the water to 23 million people in the megalopolis are greatly over-exploited. Uncontrolled urban expansion, poor land management, and pesticide-use in the watersheds that recharge these aquifers complicate the situation all the more.

Conservation International works to curb these impacts in part by creating a common dialogue among players in city, rural, and natural landscapes. For me, this has meant sometimes pulling on my boots and heading to the mountains at 5:00 am. Other times it’s meant drinking coffee with corporate sponsors in business casual.

The challenges of uncontrolled urban growth, poor land management, and pesticide-ridden farming are complicated. Development isn’t just bad; planting trees isn’t just good. When working in rural zones the goal is not to tell indigenous community members how they should envision their towns, but rather provide them with the resources and technical experience to do so as thoughtfully as possible and with natural systems in mind. Similarly, when talking with urban residents and sponsors who think that the hills should be covered with trees, we explain that the ecosystems of the watersheds are more complex than this and include native grasslands that also need to be protected, sans trees. Learning to synthesize these intricacies in our communications with colleagues and partners and in the implementation of our regional programs has been one focal point of my work this year.

Since graduating, I’ve been challenged to put my principles into practice and test out frames for ethical and effective service. Questions I posed in class, I now ask on a day-to-day basis: How can I best support community-driven environmental work in Mexico as an American? What ways can I build cultural sensitivity in how I approach conservation? Where does my voice belong and how can I uplift the voices of others?

Work trips like the one with Sapo remind me that while the mountains are indeed key to water security in the region, they are also a physical embodiment of Mexican cultural heritage. They are bigger than the articles I write, the excel sheets I analyze, or the meetings I attend. This land is home to nearly 100 indigenous communities, whose members include those with me in the truck bed. Through their experiences, I am all the more certain that the region’s future does not exist without the deep integration of traditional knowledge.

Living history fills the watershed, and at each turn, continues to teach me.

Maria is the 2017 Halper International Public Service Fellow with Conservation International. Learn more by reading her personal blog and listening to “Protecting People and Water in Mexico City,” a Making Contact radio piece she created in May, 2018.

No small task

By Noah Garcia, M.A. ’15 (Public Policy)

By Noah Garcia, M.A. ’15 (Public Policy)

I hopped off a cozy rush hour “L” train and walked into the office at the city’s Civic Opera Building for the first time. Any hazy ideas I had about the work quickly came into sharp focus: Drafting written comments and reports. Liaising with other environmental organizations and utilities. And reading way too much email.

When I accepted my fellowship with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) in Chicago, I was excited and anxious about the fellowship’s broad clean energy scope. I felt that the classes I had taken in college had prepared me, at a high level, for work that lay ahead. But so much learning took place on the job.

Moving the needle on clean energy development in the Midwest is no small task. I feel proud to have worked on NRDC teams that drove bold renewable energy and energy efficiency legislation in Illinois. I feel proud to have helped spur electric vehicle adoption in Ohio through multi-party agreements to fund critical infrastructure. And I am in awe of what I have seen my colleagues accomplish. Through it all, Stanford has been the supportive platform I have used to explore these areas of interest in the environmental sphere.

Noah was a 2015 Schneider Fellow. Schneider Fellows work at leading U.S. nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to tackle sustainable energy challenges.