Category: Community Organizing & Activism

Redesigning Justice: Transforming Housing Courts to Housing Centers

By Leya Elias, ’21

Only at Stanford could I take a class that allowed me to use legal design to create and test innovative solutions to a pressing challenge in my hometown: homelessness.

In the summer of 2019, I interned with the Public Rights Project, where I learned about the under-enforcement of consumer protection laws and the cracks within the civil justice system. After leaving my internship, I craved an opportunity that would teach me more about the civil court system, while also allowing me to work alongside community members to make improvements where needed. Luckily, I found a Cardinal Course called LAW806Y: Justice by Design: Eviction and Debt Collection. This course gave me the opportunity to explore my interests in civil courts and economic justice through a legal justice lens and design-thinking practice.

Through the class, I got to work alongside a community partner, the Judicial Council of California, and spend time learning from people—community organizers, attorneys, court staff, policymakers, landlords, and tenants—who have all touched the eviction system, for better or for worse. One stark injustice that consistently came up in all of our interviews was the disparity in access to legal representation in the court system and how, as a result, many tenants face little chance at avoiding an eviction.

While the majority of tenants do not have access to attorneys, over 60 percent of those who do are able to successfully avoid evictions. Access to legal representation is a huge unmet need for populations most at risk for homelessness. In addition to the inaccessibility of civil legal representation, tenants experiencing eviction are not only at high risk for homelessness, but are also missing a centralized support system dedicated to their success and well-being.

Since 2018, homelessness has increased 17 percent and 43 percent in San Francisco and Alameda, respectively. Witnessing the changes in my own city, I became interested in how the court could serve as the center of preventative support systems for not only those experiencing evictions, but those at risk for homelessness. Through the course, I had the opportunity to work on a facilitated holistic social services and legal aid program based in courthouses that offers resources such as rental assistance, skills training, and relocation programs.

As I work on testing my prototype alongside community partners and the Judicial Council of California, I am motivated by the potential for this program to decrease the rampant displacement across Bay Area communities. As a new family member or friend experiences eviction, displacement, or homelessness, the work I am doing in this class becomes even more pertinent and leaves me feeling honored to be able to think about how I can help.

Before the class, I saw becoming a practicing attorney as my only path toward mitigating the inaccessibility of legal representation. However, the course’s application of design-thinking to legal systems has equipped me with an innovative toolbox with which to approach systematic legal issues as an attorney. As I look forward to my senior year, I am excited to take this new experience of social justice-oriented design-thinking to my work in and out of the classroom. I am empowered not only to become an attorney, but to become an attorney capable of redesigning our country’s legal system into one that works for our most at-risk communities.

Leya Elias, ’21, grew up in San Francisco, CA. At Stanford, she studies psychology with a minor in political science and African & African American Studies. Leya completed a Cardinal Quarter in summer 2018 with the Ghana Center for Democratic Development and worked with the Public Rights Project in Oakland, CA during summer 2019 with the support of Emerson Collective. Leya is co-president of the Stanford Ethiopian & Eritrean Students’ Association and the Stanford Black Pre-Law Society, and has served as chair of the ASSU Undergraduate Senate as well as an Institute for Diversity in the Arts fellow.

Engaging the Public in Advocacy for Survivors of Sexual Violence

By Elizabeth Kim, ’22

3, 2, 1. We were rolling.

It was only my third week as End Rape on Campus (EROC)’s campus data fellow, and here I was, speaking to hundreds of people as I explained concepts that I had only grasped the nuances of a week earlier. I was aided, of course, by my boss: EROC Policy Director Ever Hanna, an attorney whose detailed knowledge of government, law, and sexual violence advocacy never ceased to awe me.

In this Facebook livestream, however, we were sitting side by side, co-hosting an informative Q&A on topics that ranged from affirmative consent to the Clery Act, a law that aims to provide transparency about campus crime policy and statistics. Though I’d spent many hours anticipating and rehearsing the answers to questions tweeted to us from all over the country, I was terrified of saying the wrong thing. Could my new understanding of this incredibly complex issue fail me, forever tarnishing the reputation of this organization that I already loved so much?

My primary project during the summer with EROC was helping establish an accessible, accurate, self-sustaining School Accountability Map, with the goal to make every U.S. college and university’s sexual assault policies and history accessible to the average college student. Because every school in the U.S. interprets Title IX differently, and few make that information accessible to students, the map will improve transparency and put power in the hands of student survivors. It was my job to develop and launch the Map Volunteer Campaign—to recruit, instruct, and vet the research of the volunteers who would collect information on each school. This livestream was meant for these volunteers, many of whom identify as survivors themselves, as they navigated the gargantuan task of researching and processing their school’s Title IX policies.

The goal of the livestream Q&A was not only to inform our volunteers, but to excite and motivate them about the work ahead. We wanted to empower volunteers with answers to their questions, but also show them that they already possessed the intelligence, courage, and persistence needed to educate their own communities about their school’s history with sexual violence.

Fun, informative, and relatable. These were the words I chanted in my head as our communications director counted down the seconds to us rolling, but soon I forgot about them. I rattled off different definitions, fielded a viewer question about due process, and chimed in on Ever’s explanation of how federal agencies can mandate different interpretations of Title IX. I felt myself falling into the rhythm that I so often enjoyed while watching talk show hosts vibe with guests they knew well.

I came out of the livestream that day not only with a more profound sense of confidence, but also an important realization: fully understanding something means you can explain it to another person. And an explanation requires a willingness to engage and put yourself out there.

This is the sort of heightened confidence I draw from as a student seeking to raise greater awareness about Stanford’s own culture of sexual violence. Whether I’m writing an Op-Ed or participating in an awareness campaign, I’ve realized that there are many ways to engage the community—each as important as the next.

Originally from Boston, MA, Elizabeth Kim, ’22, majors in economics at Stanford. In addition to her service through the Cardinal Quarter program as End Rape on Campus’s data fellow during the summer of 2019, Elizabeth serves as a French language conversation partner at the Stanford Center for Teaching and Learning and chairs philanthropy and alumni relations for Sigma Psi Zeta Sorority.

Listen Deeply and Act Strategically: Organizing for More Equitable Education in Colorado

By Tavia Teitler, ’21

I could see the majestic Colorado mountains in my rearview mirror and feel butterflies in my stomach as I pulled into the parking lot of Sister Carmen Community Center. It was my first day of work at Engaged Latino Parents Advancing Student Outcomes (ELPASO), and it only took about 10 minutes of the weekly Monday morning staff meeting for me to realize that I would be working for a truly incredible organization.

The ELPASO community organizers and school-readiness coordinators introduced themselves to me and immediately launched into a discussion about ways to effectively engage with their community in the current climate of fear about immigration. ELPASO’s then executive director, Tere Garcia, then spoke passionately about her new idea for a teddy bear clinic that could help raise awareness about the importance of preventative medical care. As I listened, I was blown away by the passion, energy, and power in the room. My sense of awe and inspiration only grew throughout the summer as I became more familiar with the women of ELPASO and the work they do.

I am majoring in comparative studies in race and ethnicity with a concentration in inequality in education, so a lot of my time at Stanford has been spent learning about theories of education inequity. However, I lacked intimate firsthand knowledge of what people were doing in their communities to tackle these issues. In other words, I didn’t know what many of these concepts and theories looked like on the ground.

ELPASO is a community organization based in Boulder, Colorado, that works to help close the opportunity and achievement gap between White and Latinx students in the area through effective parent engagement. By learning about ELPASO’s parent training and parent advocacy groups, I came to appreciate the power of informed, organized parents, and gained a deeper understanding of all of the factors that go into fighting for more equitable education. The theories I had learned about in the classroom came to life for me as I tagged along as the coordinators went door to door to recruit parents for their training program and listened as parents described their experiences raising their children in this country. I attended meetings with the parent advocacy group to ask school district officials to revise their translator policies and hire bilingual school secretaries. I also took notes as the women held a meeting with the director of the local free clinic to voice concerns about how they and the parents they work with were being treated. Later in the summer, I helped prepare materials for a workshop at a local trailer park on how to fill out money orders properly after the residents were robbed of a month’s rent by their landlord.

I was inspired by the organizers’ and coordinators’ ability to respond to more immediate needs in their community while still maintaining focus on their long-term mission. I learned lessons in the field from the women of ELPASO that both challenged and informed the lessons I’ve learned in the classroom. Most importantly, the women of ELPASO showed me what it means to listen deeply and act strategically. I know I will bring this knowledge back to the classroom, and out into the world after graduation.

This summer helped me realize that community organizing and nonprofit work, especially in relation to issues of education access and equity, is the kind of work I want to do in the future. Though I still need to spend time reflecting on my place as a White Stanford student in organizations that serve historically marginalized communities, I now know that I am committed to learning, just as I learned from my co-workers at ELPASO.

Originally from Carbondale, Colorado, Tavia Teitler, ’21, is majoring in comparative studies in race and ethnicity and psychology. Her interest in education equity led her to return to her home state for a Cardinal Quarter fellowship with Engaged Latino Parents Advancing Student Outcomes (ELPASO) during the summer of 2019. Tavia also serves as a community engaged learning coordinator at the Haas Center for Public Service and as co-chair of Ballet Folklórico de Stanford, a Mexican folk dance group on campus.

When Home is a Region: Working Towards an Inclusive Bay Area

By Nani Friedman, ’20

In my second week as an intern at Enterprise Community Partners, an organization focused on affordable housing issues, I attended a meeting of the Mayor of Oakland’s Housing Cabinet. A mix of city housing department staff and representatives from affordable housing nonprofits spent the two-hour meeting discussing the importance and challenges of incorporating racial equity components into the city’s affordable housing program guidelines. Though they weren’t able to come to a conclusive decision in two hours, and although people disagreed on the timing and implementation method, everyone was incredibly passionate and utilized their experience to offer new ideas.

I was deeply inspired and motivated by what I saw in that room. As I reflected on what was most meaningful to me this summer, I kept coming back to the constant excitement I felt spending all summer around people who shared my passion for and my perspective on the inextricable link between housing policy and racial justice.

As a regional housing policy intern, I spent most of my summer drafting legislative language and conducting research tasks for AB 1487, state legislation that enables the creation of a Bay Area Housing Finance Authority for the entire nine-county (and 101-city) region. I learned that laws are, in fact, written on Word software. I learned about the political and logistical opportunities and challenges of coordinating an affordable housing strategy at the regional level. I began developing a regional perspective, learning comparatively about the unique housing needs across different jurisdictions; the affordable housing landscape is entirely different between Oakland, Palo Alto, Fairfield, and Sonoma in the context of fire recovery, yet we worked to design a framework for a regional authority that will supplement collective needs and work for everyone. I attended convenings with people from around the Bay Area who were trying to work together to solve our regional problems.

Having grown up in the Bay Area, my work in housing justice at the local level has always felt personal. I am witnessing my friends from high school make decisions about whether or not they can afford to live on the Peninsula, while college friends who have graduated join the ranks of new tenants who are both drawn into and disgusted by the contradictions of Silicon Valley culture. Working in the financial district in San Francisco this summer gave me a new perspective into this culture, as I witnessed who actually lives and works in this region. I know that I bear unique witness to this dual perspective, the “old” and the “new.”

However, I did not anticipate that working on a state bill for a regional housing authority would make me reflect on what this entire region means to me personally. I knew that I had a deep commitment to justice in the county I grew up in, but working on housing at the regional level reframed the geographies that I include in my “home.” If custodial staff working at Stanford are commuting from Antioch, I must consider Antioch to be a part of our home. I realized that if I am going to fight towards an inclusive Bay Area – against the racial and socioeconomic segregation that occurs on a regional level – I needed to make my personal definition of home inclusive of the entire region. The futures of Richmond and Marin, for example, or Oakland and Menlo Park, are deeply connected. I now feel that I have a stake in these connections as a part of my dedication to equity in the place I call home.

Nani Friedman (she/her), ’20 grew up in Belmont, CA. With a major in Urban Studies and a minor in Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, Nani applies her studies to affordable housing issues. She has participated in an Urban Summer Fellowship (2019) and a Community-Based Research Fellowship (2017) through Cardinal Quarter. She is a founding member of the Stanford Coalition for Planning an Equitable 2035 (SCoPE 2035), a housing justice activism group at Stanford.

Reflecting on Four Years of Cardinal Service

By Callan Showers, ’19

The Cardinal Service initiative began my freshman year, in the fall of 2015. I am so thankful I made a lasting service commitment right away, by joining a Cardinal Commitment organization called Women and Youth Supporting Each Other (WYSE).

The Stanford women in WYSE facilitate weekly mentorship sessions for middle school girls in East Palo Alto and discuss topics like puberty, women’s empowerment, race and discrimination, and sexual health.

I was persuaded to apply because it seemed like a way for me to expand my sense of community and purpose at and around Stanford. This couldn’t have been truer. Engaging with the East Palo Alto community and its middle schoolers through WYSE has taught me innumerable lessons about cultural humility, community action, education justice, and leadership.

I also had the chance to engage with the broader Bay Area through the Cardinal Course, From Gold Rush to Google Bus: History of San Francisco. We worked with a community partner to identify little-known stories about the city’s history and write articles for an online historical database. I got to nurture intellectual interests through experiences such as digging through archives in the San Francisco Public Library, while also contributing to a community-based project with lasting impact. It also helped me realize that you don’t have to be from a place to help shape its history.

While these experiences connected me to parts of the local area, Cardinal Service programs also helped me serve in the place I have always called home: Minnesota.

The summer after my sophomore year, I received the Advancing Gender Equity Fellowship from the Haas Center and Women’s Community Center to work as a legal intern at Gender Justice, a public interest law firm in St. Paul. Gender Justice represents clients who have experienced gender discrimination or sexual harassment, and I got an inside look into legal proceedings such as depositions, while also getting the chance to draft policy advocacy memos and see the inner workings of a nonprofit.

This Cardinal Quarter inspired me to pursue public interest law because of how well it fit my skills and my desire to make change. I am pursuing a two-year position as a paralegal at a civil rights law firm in Washington, D.C. I truly believe without the values of community-engaged learning experiences and the way I saw my personal and professional values and skills align at Gender Justice, I would be less prepared to enter into this work and my life beyond.

Callan Showers, ’19, was in the first class at Stanford to experience four years of Cardinal Service. She co-led the student organization Women and Youth Supporting Each Other (WYSE). Callan also completed a Cardinal Quarter with Gender Justice, a nonprofit law firm, and a Cardinal Quarter from the Bill Lane Center for the American West serving with the French cinema house Galatée Films.

Callan Showers, ’19, was in the first class at Stanford to experience four years of Cardinal Service. She co-led the student organization Women and Youth Supporting Each Other (WYSE). Callan also completed a Cardinal Quarter with Gender Justice, a nonprofit law firm, and a Cardinal Quarter from the Bill Lane Center for the American West serving with the French cinema house Galatée Films.

Queer Migrant Experiences: Exploring Self and an International Community

By Alan Arroyo-Chavez, ’19

The warm summer air kissed my face as I sat on a tree-shaded hill watching the sun set between la Catedral de la Almudena and el Palacio Real. Who would have thought that a boy from Tracy, California would end up basking in the orange madrileño sun?

Then again, this was my second time in the city. When I first came to Madrid, Spain in 2017 through the Bing Overseas Studies Program, the city charmed me with its architecture, liveliness, and people. I didn’t think I would return, but then I was offered the Halper International Summer Fellowship to work with Kifkif, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to provide aid to queer immigrants in Madrid. People who seek help from Kifkif come from Europe, Latin America, and Northern Africa; they speak English, Spanish, French, Italian, Romani, and Arabic.

Immediately, I was put to work transcribing interviews that my supervisor, Florencia Rivaud, had conducted to shed light on queer immigrants’ experiences coming to Spain. In these interviews, I heard about queer people being extorted because of their identities and Latinx trans women being ostracized. I was shocked by the hardships that the people interviewed went through. However, these same people made a home for themselves in a new country, came to terms with their identities, and maintained positive attitudes. Many of these immigrants and their children return to work for Kifkif to help others settle in Madrid.

Listening to their stories forced me to break through the veil of comfort that living in the United States created. As a queer Mexican man, I see the community of queer refugees in Madrid as part of my own broader Latinx and queer community. However, we differ in a key way. In the United States, despite its own shortcomings, I can be open with my friends and my loved ones, and this safety is a privilege that I took for granted.

Laws and cultures around LGBT issues in places like Spain shift over time. Spain decriminalized homosexuality in 1979 soon after the fall of the Franco regime, legalized same-sex marriage in 2005, and instituted penalties for discrimination based on sexual orientation. (In comparison, there are still jurisdictions in the United States that protect an employer’s right to dismiss an employee based on sexual orientation). Because Spain has risen as one of the countries most accepting of LGBT people, Latin Americans immigrate to Spain. This migration is complicated and ironic given that these immigrants seek refuge from violent dynamics that Spain established in the first place.

I think a lot about how after 1492 Spain imposed Catholicism in Latin America, establishing rigid gender roles and solidifying hetero-patriarchal dynamics among indigenous peoples and their mixed descendants. Those dynamics continue to affect my community, including myself.

Though it continues to be difficult to unpack the relationship that my Latinx communities will always have with Spain, this Cardinal Quarter experience has been a gateway to learning more about the human rights issues that queer people face internationally. I hope to continue learning about the experiences of queer immigrants from countries outside the United States so that I can better connect with communities I consider my own.

Alan Arroyo-Chavez is majoring in Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity. He is a member of the Public Service Honor Society, a year-long cohort that provides seniors the opportunity to reflect on their public service and develop their civic leadership identities. In 2018, he completed a Cardinal Quarter in Madrid, Spain with Kifkif, an aid organization for queer immigrants.

Who Tells Their Stories: Questions of Ethics and Agency at the Southern Border

By Jenn Ampey, ’19

The room was tiny and filled with more people than the fire code allowed. Giant cameras stood on tripods at various heights, but all of them were tall enough to block my view.

I was attending a press conference for parents looking for children who had been taken from them by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). It was only my second day of work with Hope Border Institute, a human rights advocacy organization on the southern border, but already the whirlwind that was summer 2018 had swept me up; every day brought news of changes to U.S. immigration policy and the deepening insecurity for asylum-seekers under the Trump administration. In the crowd stood reporters from the Washington Post, CNN, and Telemundo. Microphones from the newspapers and networks sat atop their cameras, pointing at ten parents sitting in a line across the front of the room. They took turns speaking.

This press conference was my first (but not last) visit to Annunciation House, a shelter for recently arrived immigrants that was quickly becoming the center of media-to-parent interaction under the outspoken leadership of the director, Ruben Garcia. Struggling to balance engagement with the media and his desire to protect the newly arrived immigrants under his care, he stood nervously at the front of the room. As reporters jostled in front of me, I realized that many of them didn’t speak Spanish. On the other hand, the parents waiting to speak to us did not speak English.

Accepting the fact that I would never be able to see, I settled into my spot against a wall to listen, occasionally glancing up at the camera monitors overhead to get a picture of who exactly was speaking. My supervisor, Edith, stood next to me as farm labor leader Dolores Huerta arrived to take the seat that we were saving for her in the back. She lasted about five minutes of not being able to see anything before she stood up and made her way quietly through the crowd to the front, where she could look directly into the faces of the parents.

A father spoke emotionally about missing his son, eventually breaking down and sobbing at the table, while Ruben’s hand rested on his shoulder. In that moment, I noticed something that would preoccupy me for the rest of the summer. As the man cried harder and harder, the sounds of hundreds of camera shutters filled the air. It was a hot day, but I felt a chill crawl down my spine. Bile rose in my throat, and I turned my head away. For the rest of the press conference, I stared at the ground and tried to hold back angry tears and take in everything I could at the same time.

When the press conference finished, I helped my supervisor field translation requests from reporters who only spoke English but still wanted individual interviews with the parents. Eventually, we left and walked back to the car. I slid into the passenger’s seat with a migraine throbbing from the emotions of the day. A tear slid down my cheek and mixed with the sweat from Texas’s harsh summer heat. Day 2 of 45.

Jenn Ampey, ’19, is an international relations major with a minor in human rights, from Rockville, Maryland. She is the Cardinal Service Peer Advisor team lead and member of the WSD Handa Center for Human Rights and International Justice Student Advisory Board. After graduation and a gap year, she hopes to earn a joint law degree-journalism masters’ degree and help find better ways to tell the stories of survivors of human rights abuses, largely as a result of her Cardinal Quarter experience on the border.

Launching The A(bilities) Hub Initiative

By Zina Jawadi, ’18, MS ’19

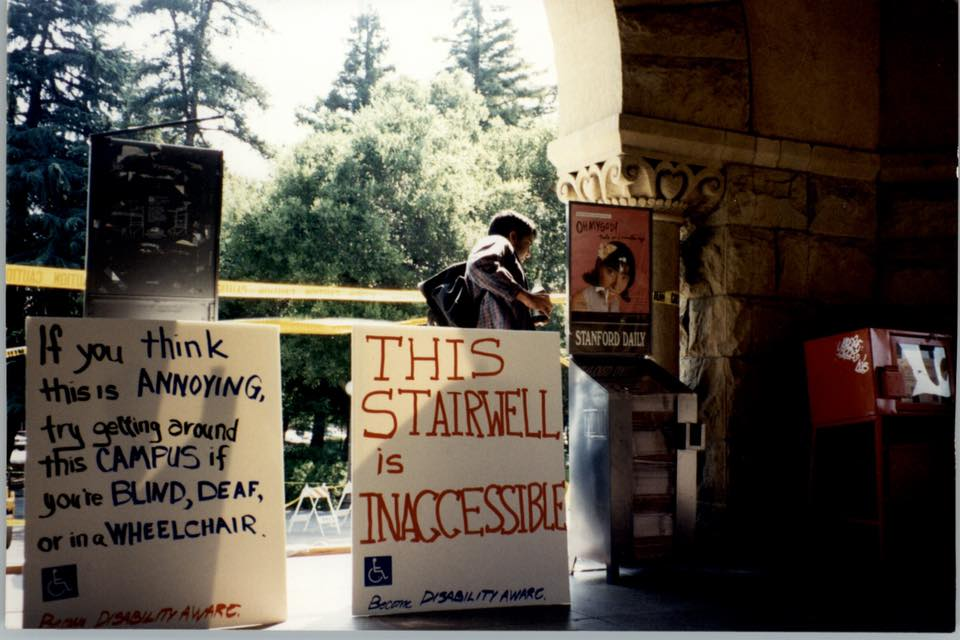

Disability advocacy efforts have been vibrant at Stanford for decades, and over the past few years, students with disabilities have resumed advocating for a disability campus center.

In 2013, Vivian Wong, ’12, realized that there was no disability community space or student organization at Stanford for students with disabilities.

She helped create a new position in the ASSU Executive Cabinet and worked with Krystal Le, ’14, to found Power2ACT, a much-needed student organization that provided a safe space for students with visible and hidden disabilities.

When I arrived at Stanford in 2014, I saw that people with disabilities still lacked a physical space. I had just worked with my high school’s administration to found a disability awareness program and thought I could draw on this experience to help make a meaningful impact at Stanford.

I am a member of several minority groups as a hard-of-hearing, Iraqi American, second-generation immigrant. My passion for disability advocacy began in the eighth grade, driving me to compete in more than 30 Original Oratory competitions and to join the Hearing Loss Association of America, California State Association. At Stanford, the skills from my nonprofit board involvement and my public speaking experience came in handy.

During my sophomore year, former Power2ACT president and ASSU Executive Cabinet member Chris Connolly, ’15, and Kartik Sawhney, ’18, reached out to help me revive the pursuit of a campus center with the ASSU Executive team. Together, we communicated to students, faculty, and administrators about the need for a physical space on campus.

I am often asked why it is important for a community to have physical space at the Farm. A physical space will allow students without disabilities to think about disability, increasing the visibility of disability and emphasizing the disability community’s place at Stanford.

In November 2017, the A(bilities) Hub Initiative was launched in conjunction with the 2017-2018 Disability Awareness Week. We were appointed an official staff advisor, Carleigh Kude, and established a student-led committee for the A-Hub.

In launching the A-Hub, I discovered the many paths that our members take to join our community, including advocacy, disability studies, personal reasons, or a family member’s experiences. Working with them, I learned how a few individuals with shared advocacy goals can make a community stronger and that unifying individual efforts can multiply the effects.

Currently, the A-Hub is a temporary space, and we are still working toward a long-term solution: an established community center with a full-time director.

Zina Jawadi is a student advocate for disabilities rights at and outside of Stanford. Zina supported the launch of the Abilities Hub in 2017 and the formation of the Stanford Disability Initiative in 2017, for which she continues to serve as co-chair. Zina was the president of Power2ACT in 2016-17 and was an ASSU Executive Cabinet member in 2016-17 and 2017-18. Outside of Stanford, Zina is active in the Hearing Loss Association of America – California State Association, serving as board member since 2013 and president since 2015. Zina is a member of the Haas Public Service Honor Society. She is from the San Francisco Bay Area.

Advocating for patients and policy change

By Brian Kaplun, ’18 (Human Biology), MS ’18 (Management Science & Engineering)

I’ve wanted to be a doctor ever since I was a kid, but it was an experience as a research assistant at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles right before coming to Stanford that showed me there is more to healthcare than a doctor’s visit. There, I met a small boy who had gone blind due to his family’s lack of consistent access to healthcare—an entirely preventable loss. Based on this experience, and the many lessons on injustice and inequity to come, my coursework, advocacy, and service over the last four years have all been part of a deeply held commitment to addressing healthcare disparities.

I started volunteering at the student-run Arbor Free Clinic my first quarter at Stanford as a Bridge to Care counselor. It was my job to find patients what the clinic couldn’t provide—from health insurance and a regular doctor to temporary housing, legal assistance, and job training. I learned how a difficult diagnosis or untreated illness could impact every aspect of one’s life, and about the potentially harmful interplay between health and sociopolitical factors—including from far too many undocumented families scared to seek healthcare out of fear of being separated and torn apart.

This was—and still is—the hardest job I’ve ever had, but it was the first time I felt like I had the knowledge base to help others. However, even after three years on the team, the sheer complexity and gaps in the healthcare system and the broader safety net meant that often our patients couldn’t get the help they needed.

I worked my way up to become clinic manager, overseeing more than 100 undergraduate and medical student volunteers. As the primary liaison to other Bay Area community health centers and agencies, I worked to strengthen collaborations to provide patient resources, including up-to-date information on topics such as immigration assistance, domestic violence resources, and pro-bono surgery options. Most importantly, in my successes and failures as a volunteer and manager, I learned that as an outsider to the communities we served, I needed to recognize my privileges and biases; the most important thing I could do was know when to listen, and to stay humble and empathetic.

As a gay man, I have struggled with less-than-inclusive care, and LGBTQ+ advocacy has been an important part of my passion for healthcare equity.

At Arbor Free Clinic, I co-led the Queer Health Initiative, a multi-year project to systematically improve services and care for LGBTQ+ people. I also served with the Human Rights Campaign on the Healthcare Equality Index, a tool focusing on inclusive hospital policies, and at Pangaea Global AIDS as a Huffington Pride Cardinal Quarter Fellow, studying the HIV policy landscape for gay men and trans women in Zimbabwe.

While one-on-one patient interactions reaffirmed my goal to be a physician, through Stanford courses on racial and ethnic health disparities, the American healthcare system, and policy analysis, I learned about the broader policy and social landscape that leaves so many patients behind. Last summer, as a Sand Hill Foundation Cardinal Quarter Fellow at Kaiser Family Foundation, I applied this learning to writing policy analysis and issue briefs about changes to the Affordable Care Act and the state of the HIV epidemic for gay and bisexual men.

In the coming year, as a 2018 John Gardner Public Service Fellow, I will staff the Democratic health policy team for the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee in the U.S. Senate, with Deputy Health Policy Director Andi Fristedt as my mentor. This committee is the battleground for many of the fights over Affordable Care Act repeal, healthcare costs, and reproductive justice, and where legislation to curb the opioid epidemic is taking shape, and I’m excited to dive into these important efforts. Following the fellowship, I will pursue a medical degree at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

At Stanford it was service that affirmed, over and over, the issues I cared about and the ways I needed to be involved. Through my Cardinal Commitment, I learned how to channel my frustration with inequity into a constructive desire to do more. As I look toward life after Stanford, I hope to continue working in both the clinical and systemic aspects of health—as a doctor healing individual patients, and as a policymaker and advocate working on the broader factors that affect their wellbeing.

Brian Kaplun was one of more than 300 students who declared a Cardinal Commitment in 2017–18.

Let’s talk

By Katie Wullert, PhD candidate

The growing political divide in this country is news to no one, but we are often able to avoid the ramifications of this in our private lives by surrounding ourselves with like-minded people and inhabiting ideologically homogeneous social spaces online and in the real world. Every year on the fourth Thursday in November, however, it becomes hard to prevent the political divide from intruding into our private lives as liberal nieces go toe-to-toe with conservative uncles and conservative cousins face off against progressive aunts. The Thanksgiving dinner table has become a notorious place of political contention. This political showdown is not playing out in Washington or on Fox or MSNBC, but in our own homes. What do we do about this contention when it is finally right in front of our faces? If we follow the model of Saturday Night Live, perhaps we play Adele to soothe the room and prevent any conflict from escalating. But what if, instead, we dug into that tension?

That was the premise behind a series of three, hour-long dinner conversations held at the Haas Center this past February. Students with differing political perspectives were brought together to discuss issues that we often do not talk about across political divides. The conversations covered the American Dream, immigration, and freedom of speech vs. controlling hate speech, and students were asked to present their views thoughtfully and listen to the views of others around them. My role in this was to facilitate, provide guiding questions, make sure there was food and the room was ready, and let the conversation unfold as it did. From my perspective as an observer of each of the conversations, one theme clearly emerged: finding common ground is easier than digging into divisions.

As the participants got more comfortable with each other and with the conversations, greater disagreement did emerge, but it is hard to break down the walls of kindness that suggest we should not butt heads with others, and it is comforting to find that the conversation fit into a groove in which people can fundamentally agree. After each dialogue, students expressed their surprise at the fact that there was so much agreement. On one hand, this was a real positive. Students discovered that people they had assumed to hold one opinion actually believed something very different, and two individuals who might have been presumed to be at odds were in fact much more in alignment with each other than expected. On the other hand, the students also noted that they felt there was more there that was never fully discussed, points of contention that were never brought out fully in the open but remained under the surface as if Adele was softly singing to keep tempers in check.

Around another dinner table, the conversations certainly might have looked very different, but the experience of this dinner table left me with one question: when we attempt to come together across political divides, what is the goal? Are we searching for agreement to remind ourselves we are all people? There’s value to that, but also the very real risk of dismissing disagreement that should not just be brushed aside and ignoring views that perhaps can never be reconciled but have immense impact on people’s lives and experiences. Are we instead looking to debate and perhaps even let our tempers flare up as we speak passionately about issues we care about? This ensures we do not ignore important divisions, but also may make us miss places where we do agree as we presume that by knowing one opinion someone has, we know every political view they hold. After watching and reflecting on these three dialogues, the best answer I could come to is that we have to start the conversation and then let it unfold as it does. That is what this group of students did; they were honest and open, and even if certain things were left unsaid, they came out having learned something and hopefully feeling readier for the next conversation and wherever that takes them.

Around another dinner table, the conversations certainly might have looked very different, but the experience of this dinner table left me with one question: when we attempt to come together across political divides, what is the goal? Are we searching for agreement to remind ourselves we are all people? There’s value to that, but also the very real risk of dismissing disagreement that should not just be brushed aside and ignoring views that perhaps can never be reconciled but have immense impact on people’s lives and experiences. Are we instead looking to debate and perhaps even let our tempers flare up as we speak passionately about issues we care about? This ensures we do not ignore important divisions, but also may make us miss places where we do agree as we presume that by knowing one opinion someone has, we know every political view they hold. After watching and reflecting on these three dialogues, the best answer I could come to is that we have to start the conversation and then let it unfold as it does. That is what this group of students did; they were honest and open, and even if certain things were left unsaid, they came out having learned something and hopefully feeling readier for the next conversation and wherever that takes them.

Katie is a third-year PhD student in sociology studying gender and labor market inequality and hopes to graduate in 2021-22. She is currently a Graduate Public Service Fellow at the Haas Center.