Category: Community Engaged Learning

Revisiting Milwaukee: Learning About My Hometown Through Service

By Elyse Cornwall, ’22

The first time I drove to Moody Park, I suppressed my nerves about driving into an area known for reckless driving. I reminded myself that these feelings came from racist assumptions about a community I had never meaningfully interacted with. Still, I stopped at green lights as oncoming cars ran the red, and rushed down main streets to keep other cars from skirting past me. Thus, I arrived at Moody Park feeling simultaneously afraid and embarrassed, and that was when the youth participants arrived. My primary responsibilities were event planning and coordinating with other volunteers, but I realized that my work behind the scenes could not be effective until I immersed myself in the community I served. When I ate meals, played games, and shared stories at Moody Park, a new side of my service experience emerged.

My weekly discussions with youth living near Moody Park covered topics like drugs and alcohol, police relations, and reckless driving. The group’s familiarity with dangerous situations seemed to contradict their charisma and friendliness. I helped host the Zeidler Center’s listening circle events, which allowed youth and police officers from the area to talk with each other in small groups. The youth took turns responding to prompts such as, “Describe an experience you have had with a police officer,” sharing their experiences rather than debating or convincing anyone. The Zeidler Center hosts listening circles like these throughout the Greater Milwaukee Area, featuring topics like political polarization, race relations, and education. These events are based on the organization’s belief that open, respectful dialogue promotes positive change. I watched as the listening circles at Moody Park shifted from short responses to candid conversation. By the end of the discussions, youth and officers were sharing accounts of their days and stories of hardship, relating to one another on a personal level.

As an outsider in this community, I felt hesitant to expand beyond my role as a staff member, but eventually gave in with the encouragement of the youth and other staff. I shared my own experiences, admitted the gaps in my knowledge of Milwaukee, and put myself in a position to learn from the youth I had aimed to serve. Not only did I feel more connected to a community that I hadn’t interacted with before, but I also felt a stronger obligation towards my city. I found that my view of civic duty and participation changed once I got to know the people with whom I was sharing a community.

By the end of the summer, I started to see my service experience in connection to my parents’ work in Milwaukee as public servants. Usually, I thought of my parents as lawyers who happened to work for the state and county. Though they had expressed pride in serving those who relied upon public legal assistance, I never thought of their occupations as reflections of their character. As a court commissioner, my father has the opportunity to combat the racial bias that targets people with his racial identity in most courtrooms. Like my father, the staff and volunteers at the Zeidler Center prioritize listening to and learning from the communities they serve.

I am glad to have developed this new civic understanding in the context of Milwaukee, through the service I have done. When I returned to Stanford in the fall, I brought with me a willingness not only to serve, but also to know the people within my community who are most targeted and misrepresented.

Elyse Cornwall, ’22, studies computer science at Stanford. Originally from Milwaukee, WI, Elyse completed a Cardinal Quarter in her hometown the summer after her freshman year, working to support the Zeidler Center, an organization that fosters civil dialogue across perspectives. At Stanford, Elyse is a CS106A section leader; a team leader for Ideas Out Loud, Stanford’s TEDx club; and a member of the Delta Delta Delta Sorority.

Redesigning Justice: Transforming Housing Courts to Housing Centers

By Leya Elias, ’21

Only at Stanford could I take a class that allowed me to use legal design to create and test innovative solutions to a pressing challenge in my hometown: homelessness.

In the summer of 2019, I interned with the Public Rights Project, where I learned about the under-enforcement of consumer protection laws and the cracks within the civil justice system. After leaving my internship, I craved an opportunity that would teach me more about the civil court system, while also allowing me to work alongside community members to make improvements where needed. Luckily, I found a Cardinal Course called LAW806Y: Justice by Design: Eviction and Debt Collection. This course gave me the opportunity to explore my interests in civil courts and economic justice through a legal justice lens and design-thinking practice.

Through the class, I got to work alongside a community partner, the Judicial Council of California, and spend time learning from people—community organizers, attorneys, court staff, policymakers, landlords, and tenants—who have all touched the eviction system, for better or for worse. One stark injustice that consistently came up in all of our interviews was the disparity in access to legal representation in the court system and how, as a result, many tenants face little chance at avoiding an eviction.

While the majority of tenants do not have access to attorneys, over 60 percent of those who do are able to successfully avoid evictions. Access to legal representation is a huge unmet need for populations most at risk for homelessness. In addition to the inaccessibility of civil legal representation, tenants experiencing eviction are not only at high risk for homelessness, but are also missing a centralized support system dedicated to their success and well-being.

Since 2018, homelessness has increased 17 percent and 43 percent in San Francisco and Alameda, respectively. Witnessing the changes in my own city, I became interested in how the court could serve as the center of preventative support systems for not only those experiencing evictions, but those at risk for homelessness. Through the course, I had the opportunity to work on a facilitated holistic social services and legal aid program based in courthouses that offers resources such as rental assistance, skills training, and relocation programs.

As I work on testing my prototype alongside community partners and the Judicial Council of California, I am motivated by the potential for this program to decrease the rampant displacement across Bay Area communities. As a new family member or friend experiences eviction, displacement, or homelessness, the work I am doing in this class becomes even more pertinent and leaves me feeling honored to be able to think about how I can help.

Before the class, I saw becoming a practicing attorney as my only path toward mitigating the inaccessibility of legal representation. However, the course’s application of design-thinking to legal systems has equipped me with an innovative toolbox with which to approach systematic legal issues as an attorney. As I look forward to my senior year, I am excited to take this new experience of social justice-oriented design-thinking to my work in and out of the classroom. I am empowered not only to become an attorney, but to become an attorney capable of redesigning our country’s legal system into one that works for our most at-risk communities.

Leya Elias, ’21, grew up in San Francisco, CA. At Stanford, she studies psychology with a minor in political science and African & African American Studies. Leya completed a Cardinal Quarter in summer 2018 with the Ghana Center for Democratic Development and worked with the Public Rights Project in Oakland, CA during summer 2019 with the support of Emerson Collective. Leya is co-president of the Stanford Ethiopian & Eritrean Students’ Association and the Stanford Black Pre-Law Society, and has served as chair of the ASSU Undergraduate Senate as well as an Institute for Diversity in the Arts fellow.

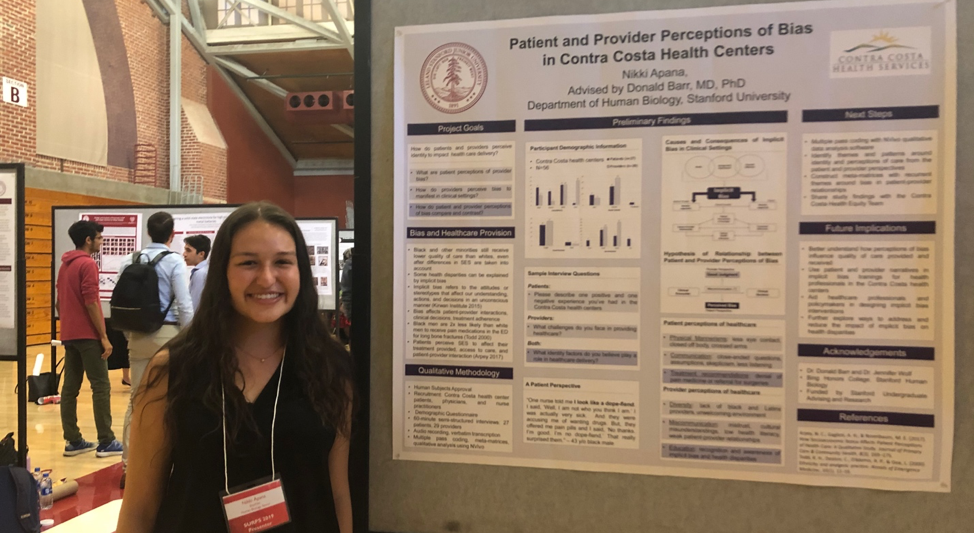

Unequal Treatment: Exploring Unconscious Bias in Health Care

By Nikki Apana, ’20

“One nurse told me I look like a dope fiend. I said, ‘Well, I am not who you think I am.’ I was actually very sick.… And they were accusing me of wanting drugs.” – James (pseudonym), 43-year-old Black male

James is a participant in the community-based research project I have been conducting over the past three summers. I have been collaborating with Contra Costa Health Services, the public health system in my hometown, to find ways to address unconscious bias in patient care. Unconscious bias refers to the stereotypes we internalize that affect our behavior, judgments, and actions without our conscious awareness. And what is so pernicious about unconscious bias is that everyone has it, yet few realize it.

Unconscious bias covertly plays out in our everyday lives. As described in Howard Ross’s Everyday Bias, NBA referees call more fouls against Black players than White players, famous Black actor Danny Glover reported struggling to hail a New York City cab after dark, and job applicants with “Black” names are less likely to receive a callback than applicants with “White” names. Bias extends beyond race to gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, age, and weight. It surrounds us every day and it is embedded in our subconscious. Even when we think we treat everyone equally, pride ourselves on promoting equality, and call ourselves feminists, queer allies, and social justice activists, unconscious bias still pervades our minds and actions.

Bias is particularly injurious in the provision of health care. Even after differences in socioeconomic status are taken into account, Blacks and other minorities still receive lower quality of care than Whites. Innumerable studies in the American Journal of Public Health and Annals of Emergency Medicine show how bias can impact clinical decisions. Physicians tend to rate their Black patients as less intelligent, more likely to abuse drugs and be non-compliant with treatment, and less likely to desire an active lifestyle and have adequate social support. Minority children with accidental injuries are three times more likely to be reported for suspected child abuse than their White counterparts. Additionally, Black and Hispanic patients are two times less likely to receive pain medication in the emergency department than White patients.

James shared a similar account of being accused of seeking drugs and being denied pain medicine while seeking emergency treatment for a liver condition. His narrative is just one of many that I collected through the community-based research project.

This project grew out of a community need to address unconscious bias. During my first summer as a Community-Based Research Fellow through the Haas Center, I helped the Contra Costa Health Equity Team develop an unconscious bias training curriculum for health-care providers. The training has been piloted with over 500 providers and continues to raise awareness about the detrimental effects of provider bias. However, many participants have still expressed concerns about learning how to mitigate their bias in the clinical setting. I consulted with members of the Health Equity Team, and together we developed the next stage of research: interviewing patients and providers about their perceptions of unconscious bias in the health centers. This study seeks to center the voices of populations that have been historically marginalized and silenced. It will also identify concrete examples of insensitive behaviors in order to offer providers specific tools for reducing unconscious bias. I have already conducted 56 interviews with patients and providers, including the one with James, and have been qualitatively analyzing these transcripts over the last two quarters with the support of the Haas Center Public Service Scholars Program and my honors thesis advisors, Donald Barr and Jennifer Wolf. In the spring quarter, I will finish writing my honors thesis and deliver a presentation and report to Contra Costa Health Services with suggestions for improving the implicit bias training.

Community-based research has taught me the value of placing community needs at the forefront of identifying problems and enacting change. More specifically, this project with Contra Costa Health Services has given me the opportunity to explore unconscious bias in medicine, as well as my own unconscious bias. I am slowly becoming more aware of my own biases and more capable of stopping biased thoughts in their tracks. All the stereotypes we have learned can be unlearned once we recognize the ways in which we hold biases, foster dialogue about unconscious bias, and continue to acknowledge privilege and self-reflect on our actions and attitudes. Biases can be broken. With time and effort, injustices like those James has faced will become the exception rather than the norm.

You can find out more about your unconscious mind and take an Implicit Association Test (IAT) at Harvard’s Project Implicit.

Nikki Apana, ’20, studies Human Biology with a concentration in race, ethnicity, social class, and public health, and a minor in Spanish. Originally from Concord, California, Nikki has spent the last three summers in her hometown working as a Community-Based Research Fellow through Cardinal Quarter on issues of bias in the health-care system. At Stanford, Nikki serves as the lead Cardinal Service Peer Advisor, president of the Polynesian dance team Kaorihiva, and residential assistant in Branner Hall. Nikki has also worked as a SHAR(ED) volunteer throughout her Stanford career, was a Branner Hall Service Scholar, serves as a Cardinal Free Clinics Patient Health Advocate, and is a member of the Public Service Scholars Program.

Global Engagement: Engineering Solutions for Sustainability

By Adam Nayak, ’22

Ever since I was little, I have been fascinated with water. I grew up four blocks from Johnson Creek, a local stream in southeast Portland, Oregon. My mom took me down to the park to play in the water, letting the currents wrap around my legs as I searched for tadpoles and capered with dragonflies.

Each month, my family would wake up early in the morning to work with our local watershed council, removing invasive species, planting native species, and picking up trash around the stream.

It was here that my younger sister and I learned about the great salmon migration. I remember being fascinated with the fish: their perseverance, determination, and tenacity, traversing upstream to their birthplace to continue their lineage. As a boy, I was always searching for salmon, but as an urban stream, Johnson Creek faced serious water-quality challenges due to a history of pollution, and I was never able to find any fish.

As I grew older, I developed an interest in the science behind water treatment and ecological systems, looking for solutions to problems of contaminated stormwater and habitat loss. Volunteering with the Johnson Creek Watershed Council was one of my most rewarding experiences, instilling in me a value for public service and community engagement that has grown with me at Stanford.

Through my involvement in Engineers for a Sustainable World (ESW), a Cardinal Commitment student organization, I have been able to pair my interest in environmental conservation with engineering practice. In particular, I worked on a small team of students during a two-quarter Cardinal Course to design and prototype sustainable infrastructure solutions in Chavín de Huántar, Perú, an archaeological site in the Andes Mountains. Through the Cardinal Quarter program, I traveled to Perú with my team this past summer to implement the project and promote cultural conservation.

Our green roofs and modular tensile structures were designed as a new approach to flood mitigation in a rural setting, with a focus on aesthetic integration of roofing structures at a culturally significant site. This opportunity not only strengthened my Spanish language and communication skills, it allowed me to collaborate with engineers and community members, as well as to learn about engineering practices in the context of a different culture and setting.

Service is powerful to me because it establishes a sense of community and belonging. As a student who is passionate about equity and inclusion, I hope to work on sustainability projects in diverse communities worldwide. The experience in Perú has enhanced my ability to collaborate on a team that spans cultural backgrounds and has reaffirmed my passion for public service projects.

Now as a sophomore, I co-lead international ESW projects focused on sustainable engineering and equitable development. They have brought me back to the theme of water, leading a project with community partners in Ghana focused on organic waste mitigation and water treatment through biochar production for carbon filtration.

For me, service involves building relationships and working collaboratively, whether internationally with an organization like el Ministerio del Cultura de Perú, or locally with the Johnson Creek Watershed Council. Both experiences involved a long-term commitment to addressing community needs. From these experiences, I have come to focus on promoting equitable access to resources for all communities, regardless of background. Looking forward, I hope to continue my work in sustainable development as an environmental engineer, focusing on clean water and equity practices in the public sector.

Adam Nayak, ’22, studies civil and environmental engineering. Originally from Portland, Oregon, Adam’s childhood interest in environmental sustainability has led him to pursue a Cardinal Quarter in Perú, enroll in Cardinal Courses, make a Cardinal Commitment with Engineers for a Sustainable World, and serve as a Cardinal Service peer advisor. Adam has also been involved in the Multiracial Identified Community at Stanford; Stanford Strategies for Ecology Education, Diversity, and Sustainability; Students for the Liberation of All People; and Students for a Sustainable Stanford.

Our Islands, Our Stories: Oral History and Community-Building in Southeast Alaska

By Regina Kong, ’22

We were inside Taiga’s fishing boat, docked at the back of the cove. I remember taking a deep breath before setting the voice recorder down on the wooden table. The boat swayed side to side with the afternoon currents. Behind Taiga, I could see thickets of salmonberries and wild blueberries. According to the locals, the dense vegetation sheltered bears that roamed the island. I began the interview by asking Taiga about his childhood, and from there, I followed him as he spoke about everything from commercial fishing to ecology to fatherhood. To this day, everything about that experience and that summer feels entirely surreal.

Taiga was one of 15 people I interviewed for an oral history project I conducted through an internship with the Inian Islands Institute, a nonprofit experiential field school in Southeast Alaska that engages students in climate advocacy and sustainability. I found Inian as if by fate. When I reached out to Inian’s director, Zach Brown, PhD ’14, a few months prior to the summer of 2019, I learned that they had wanted to do an oral history project for a while, but had never had the capacity to do so.

“Do you think you would like to do this?” Zach asked me during one of our initial phone calls.

“Absolutely,” I said.

From a young age, I have always loved stories, especially those involving multiple generations and cultures. When I began thinking about interning with Inian, I was halfway through my freshman year and already thinking deeply about what a true education meant and what forms of wisdom could be attained outside of the traditional classroom—questions that I discovered resonated with Inian’s own mission.

And that was how, not even a week after the last day of school, I found myself in the breathtaking Southeast Alaskan wilderness, surrounded by endless swathes of forest and ocean. For the rest of the summer, I traveled by boat or seaplane to various communities, collecting stories surrounding the island’s homestead, fondly known by local fishermen as the “Hobbit Hole.” My goal was to preserve important community narratives containing such rich anthropological, ecological, and cultural histories; in the process of doing so, I realized that I was also preserving something much deeper.

Oral histories are a methodology for recording and preserving information not found in written records. Because they are shaped by the contours of an individual’s experience and reflections, they allow for the unearthing of rich and often unexpected stories. While these interviews proved emotionally intense, they also taught me how to listen deeply, how to be fully present. I heard incredible stories and met the wisest and most generous people. Strangers like Taiga shared their homes and lives with me, and I will always be grateful for that. From the changing climate in Southeast Alaska to the area’s geologic history to diverse definitions of home, I found myself continually learning more about this unique community as well as discovering a greater human narrative of love, endurance, and connection.

I know this summer will continue to shape who I am for the rest of my life, and I hope to take these stories and gleams of wisdom with me wherever I am in the world. To Taiga and everyone else who made this experience as special as it was and continues to be, thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Regina Kong, ’22, is from Berkeley, California, and is currently studying comparative literature and art practice at Stanford. She spent the summer of 2019 gathering oral histories from locals in Southeast Alaska as part of the Donald Kennedy Summer Projects Cardinal Quarter fellowship with the Inian Islands Institute. At Stanford, Regina serves as a producer for the Stanford Storytelling Project and works as a student tour guide.

How an Urban Studies Class Made Me a Better Engineer

By Katherine Erdman, BS ’19, MS ’20

As the countdown to graduation began, I, like many other Stanford seniors, was eager to complete my general education Ways of Thinking/Ways of Doing. As I planned my fall quarter, I was on the hunt for a class that satisfied my last unfulfilled requirement: Engaging Diversity. There were almost 200 classes to choose from, but I settled on Urban Studies 164: Sustainable Cities. I had a mild interest in environmental technology, so I decided to give it a go.

On the first day of class, I was surprised that the focus of the course wasn’t on hydrogen fuel cells and electric cars. Rather, environmental health was just one of four aspects of sustainability we would be tackling, in addition to cultural continuity, social equity, and economic vitality. This broadened definition of sustainability, going beyond greenhouse gases and air quality indexes, was especially meaningful on the day we talked about transportation in the Bay Area. Like many other computer science students, I spent a summer interning at a large technology firm just miles from campus. I did not have a car and benefited from the shuttle service provided as part of the job. Every morning, I walked a few minutes to the nearest stop, hopped on the bus, and arrived to work without issue. I brought this up as an avenue to increase sustainability. The buses were quite full and eliminated at least hundreds, if not thousands, of mostly single-occupancy cars from the road. While my classmates agreed that the shuttles helped with environmental health, I was challenged to also consider the soaring housing prices near newly placed shuttle stops that make longtime residents unable to afford to stay. They are often replaced by tech workers, eager to be closer to the shuttle stop and able to afford higher rent. Perhaps certain shuttle stops trade off cultural continuity in pursuit of sustainability?

Through many eye-opening discussions, I more clearly saw the effects of sustainability efforts within the social and cultural realms by the end of the quarter. I walked away with a new perspective, which I applied to my senior project class CS210: Software Project Experience with Corporate Partners. My CS210 team partnered with Oracle and was given the task of creating social good technology. We decided to tackle the issue of employment opportunities for formerly incarcerated individuals. Within this space, it’s easy to identify unmet needs, such as the need for technological education for someone who has been disconnected from the job market for a number of years or the need for mock interviews for someone who has never formally applied for a job before. However, my experience in Urban Studies 164 helped me understand how any solution has to fit within a larger ecosystem. I found that my team and I were challenged to look beyond economic vitality and consider the cultural continuity and social equity concerns that our solution had to address. Whether integrating our solution into the parole preparation process for the incarcerated in Australia or modifying the product’s user interface to be approachable for first-time digital users, our team attempted to address cultural and social issues that appear tangential, but are deeply connected to the product’s success.

Katherine Erdman, BS ’19, is a coterminal master’s student in computer science from Ellicott City, Maryland. During her senior year, she took Urban Studies 164: Sustainable Cities, a Cardinal Course that introduces students to sustainability concepts and urban planning as a tool for determining sustainable outcomes in the Bay Area. Katherine has been involved in the Business Association of Stanford Entrepreneurial Students, SHIFT: Healthcare Innovation @ Stanford, and she++. She is also a member of the Student Alumni Council and the Viennese Ball Steering Committee.

Beyond the Stethoscope: Addressing the Social Determinants of Health

By Nikki Apana, ’20

For my uncle, no level of mental health treatment could cure his chronic homelessness. No number of visits to the psychiatrist could shield him from the physical and psychological trauma that accompany living on the street. Having witnessed the effects of homelessness on my uncle’s overall wellbeing, I became deeply committed to addressing healthcare disparities through medicine and public health.

At Stanford, I sought out courses that could help me understand my uncle’s experience and how to help. My frosh year I found a Cardinal Course that allowed me to combine my academic interests in public health and passion for public service: Social Emergency Medicine and Community Engagement. In the class, we discussed how socioeconomic status affects health status, and I got to see how these trends play out in the emergency room (ER) through a partnership with our partner organization, Stanford Health Advocacy and Research in the Emergency Department, or SHAR(ED).

The emergency room is a safety net. When people don’t have anywhere else to go, that’s where they end up. Sometimes emergency room patients come in for something as minor as a cold—or a serious condition after a minor condition goes unmanaged for a long time. The hospital ranks the severity of a patient’s condition on a scale of one to five, with one being the most severe. But the ranking says little about the social causes of their illness.

As a volunteer, I screened patients at the Stanford Hospital Emergency Department for social needs that could negatively affect their health. Some of the most common issues included the lack of affordable housing, difficulty accessing a primary care physician, high cost of childcare, lack of healthy food, and difficulty paying utility bills. At the end of each visit, I referred patients to local organizations to help reduce the burden of these needs on their overall health.

I valued providing patients with resources to help them cope with different pressures and reduce the frequency of their visits to the emergency room. However, in medicine there is still a disconnect between physicians and patients: ER physicians are there to only treat serious medical conditions, while patients want any treatment.

During one of my volunteer shifts, I was with a Spanish-speaking patient and a nurse asked if I spoke Spanish. I nodded.

“Oh great! Can you translate for me?” the nurse asked. Then she quickly rattled off a number of test results to me. “Her CT scans, blood test, and everything else look normal. Can you tell the patient that everything is fine and that she should just go see her primary care physician?”

I did as the nurse said. Then, the patient looked at me and asked, “Are you sure there’s nothing wrong?”

From an operational standpoint, the nurse was right; the patient should have gone to a primary care physician instead of the ER. But this patient was like many others in the ER who have never heard of a primary care physician or simply cannot afford it.

As I learned from a young age, addressing medical issues requires so much more than scrutinizing physiological symptoms and abnormalities. Access to healthy food, affordable housing, and high-quality healthcare all contribute to individual health and wellbeing and can prevent frequent visits to the emergency department.

After taking this Cardinal Course, I pursued honors thesis research on the barriers patients face in seeking healthcare—research that I plan to use to advocate for policies that ensure patients’ basic right to high-quality healthcare.

As I look beyond graduation, I hope to apply to medical school and become a primary care physician, with the knowledge that a state of complete health cannot be achieved without remediating the underlying social challenges that patients face everyday.

Nikki Apana, ’20, is a premed student studying human biology, with a concentration in race, ethnicity, social class, and public health. She is a Cardinal Service Peer Advisor, Community-Based Research Fellow, volunteer with SHAR(ED) and, patient health advocate with Cardinal Free Clinics. She is also involved with Kaorihiva, the Polynesian dance group at Stanford. Nikki is from Concord, CA.

A New Yorker Embraces the Urban-Rural Divide

By Hannah Zimmerman, ’21

I could never get over the sky in northern Michigan. One day, standing beside a trailer park after interviewing residents of an affordable housing project, I looked up at the sky. It was so blue and beautiful, and the trees that provided shade for the park residents were so full and lush. The trailers’ taped-up windows and cigarettes smashed into the ground seemed out of place. I looked back down to fasten the snaps on my red notebook, which contained my handwritten notes from interviews with 15 residents of the trailer park.

This past summer, as a research fellow for Stanford’s Anthropology department, I conducted ethnographic field research in Emmet County, Michigan. Emmet County has been unable to adapt to large economic and environmental shifts affecting northern Michigan. There have been massive factory shutdowns: the lumber industry that employed the northern half of the county has been depleted, and thousands of jobs have been lost in the last 15 years. Since 2015, the poverty and crime rates are growing faster than the state average, and 25 percent of the county’s young people have left the area. This area was also the part of the state where my grandmother grew up. Going back was not only a way to explore issues that I had been studying in an anthropology class but to connect with my roots.

In my research, I asked how people in different communities and of different socio-economic groups perceived poverty in Emmet County. This process brought me into lakefront houses and the halls of local government buildings, and—on that day at the trailer park—face-to-face with rural poverty.

Although I had tried adjusting to local customs, the few weeks spent in Emmet County had been a test for me, as I tried to conduct research outside of my comfort zone. As I sat among the trees and going over the interview notes, a man came over and asked if I was okay. I automatically flinched at the sight of his gun, perched in a holster on his belt. Growing up in New York City, carrying a weapon openly is illegal; the only interaction I had with firearms growing up was watching them used as weapons in movies. A few weeks earlier, a shop owner told me that I should just assume people have a gun on them and be surprised when they don’t. In both small and big ways, I saw how different my worldview was.

Rural poverty was nothing like the poverty I had observed in my home of New York City or in the other cities where I had worked. Rural poverty was spread out and generational. According to many residents I interviewed, the idea of getting out of poverty didn’t seem at all possible. In fact, after cross-checking all 15 interviews, I found that no one who spoke to me thought they could get out of poverty legally. This was a side of America, of poverty, that I couldn’t have imagined existed or would have been able to truly understand by reading articles about it written by New York- or Washington, D.C-based news outlets.

As an anthropology major, you’re asked to consider your own perspective as well as the perspective of others in order to understand complex issues. The rural fieldwork was challenging but it was a powerful introduction to thinking about issues from both an urban and rural perspective. This is important as I continue to work in national politics, because understanding the rural-urban divide is key to enhancing democracy at varying levels of government.

When I returned to campus this year, my friend and I have continued discussing the urban-rural divide: she, someone from rural Illinois and who worked in Washington D.C, and I, a New Yorker who worked in rural Michigan. Together, we are co-writing a piece about this divide and how we understand each other, and this is challenging us to confront our own biases.

Hannah Zimmerman is a sophomore majoring in public policy and anthropology. In summer 2018, she worked as a research fellow in Stanford’s Department of AnthropologyMichigan. She was involved in the Haas Center’s Public Service Leadership Program and has served on Stanford Rural Engagement working group as part of the University’s Long-Range Planning. She is currently a co-chair of the Stanford Student and Labor Alliance, and Stanford Coalition for Healthcare Reform. She is from New York City.

Research + community engagement

By Christopher Rodriguez, ’17 (Human Biology)

Pale wisps of steam flutter and twirl above the cup of tea on the table before me. The living room is narrow; the floor is rough, faded; the chairs feel like boulders. Sunlight scarcely saunters in through the window.

Beside me, Lilia Perez speaks in a soft cadence. She is the director of a branch of Samusocial Peru located in the secluded district of Ate-Vitarte, and my community partner. Lilia comforts a woman who holds back tears. She reminds me that most of these women are not normally granted the opportunity to disclose their abuse experiences.

This past summer, my goal was to better understand the resources that survivors of violence against women in suburban Peru find most useful to facilitating their social reintegration. The Public Service Scholars Program at Stanford has offered me the avenue through which to intersect scholarly research with community engagement.

Interviewing survivors of interpersonal violence was not easy. When they were not hesitant to share their stories, they delivered years of silent suffering in a flurry of crackling words. But as painful as it was to hear these stories, I do not forget how meaningful this research is.

The Public Service Scholars Program is a year-round program that supports students’ efforts to write a thesis that is academically rigorous as well as informed by and useful to specific community organizations or public interest constituencies.

Research rooted in public service

by Ashley Jowell, ’17 (Human Biology) and Sharon Wulfovich, ’17 (Human Biology)

The sun was setting upon Arusha, Tanzania, as we joined together for an evening discussion. We, along with our translator, Jenipher, and project manager, Sianga, enjoyed our home cooked meal in celebration of completing our 16th interview. Our faces were glowing as we sipped our tea, finished our last bites of mchicha, and discussed the data we collected as well as its potential impact. The stories Maasai women shared had been informative, alarming, and inspiring as they described the impact that moving to Arusha from their village had on their lives. How, we discussed, might we use this research to benefit the women facing such hardships upon migrating? This was a conversation we would continue to grapple with throughout our entire project and on-campus conversations.

Our research, designed in collaboration with The Future Warriors Project, a Maasai-run NGO created by Sianga, involved interviewing female Maasai migrants who had moved to Arusha. While both researchers were looking at the impact of this journey on their health, Sharon’s project focused on health decision making behavior and Ashley’s focused on resilience and identity. As the four of us bounced ideas, we felt honored to conduct research that strove to benefit the community we were so privileged to serve.

Ashley is a member of the Public Service Scholars Program at the Haas Center, where she has continued engaging in discussions on scholarship & ethical service.